Toxic chemicals found in oil spills and wildfire smoke detected in killer whales

Southern Resident killer whales. Photo: Josh McInnes

A study published today in Scientific Reports is the first to find polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in orcas off the coast of B.C., as well as in utero transfer of the chemicals from mother to fetus.

“Killer whales are iconic in the Pacific Northwest—important culturally, economically, ecologically and more. Because they are able to metabolically process PAHs, these are most likely recent exposures. Orcas are our canary in the coal mine for oceans, telling us how healthy our waters are,” said senior author Dr. Juan José Alava, principal investigator of the UBC Ocean Pollution Research Unit and adjunct professor at Simon Fraser University.

Transient killer whales. Photo: Josh McInnes

Researchers analyzed muscle and liver samples from six Bigg’s, or transient, killer whales and six Southern Resident killer whales (SRKWs) stranded in the northeastern Pacific Ocean between 2006 and 2018. They tested for 76 PAHs and found some in all samples, with half the PAHs appearing in at least 50 per cent of the samples. One compound, a PAH derivative called C3-phenanthrenes/anthracenes, accounted for 33 per cent of total contamination across all samples. These forms of PAHs, known as alkylated PAHs, are known to be more persistent, toxic, and to accumulate more in the bodies of organisms or animals than parental PAHs.

No one has studied PAHs in killer whales in B.C. before. However, the researchers noted the average level of contamination in their study was lower than previous studies of cetaceans in the Gulf of California, and almost two times higher than that found in blood samples of captive killer whales from Icelandic waters.

Southern Resident killer whales. Photo: Josh McInnes

SRKW contaminants largely from human emissions

The contaminants in Bigg’s killer whales were mostly those produced by burning coal and vegetation, as well as forest fires. In SRKWs, they were the kind produced by oil spills and burning of fossil fuels like gasoline. The researchers say this could be due to the animals’ differing habitats. Bigg’s killer whales range from California to southeastern Alaska and into the North Pacific Ocean, while SRKWs stay closer to more polluted urban environments around the Salish Sea.

Feeding preferences, behaviour and metabolism could also impact the amount of contaminants accumulating in the animals.

“B.C.’s coast is experiencing oil pipeline developments, oil tanker traffic, industrial effluents, forest fires, stormwater runoff and wastewater,” said first author Kiah Lee, who conducted the work as an undergraduate student at UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF) and is now a masters student at the University of Oslo. “These activities put toxic PAHs into the marine food web and, as we saw here, they can be found in orcas, the apex predator.”

Improve pollution management

“There’s only a small population to draw from—74 individuals in the case of the Southern Residents,” said co-author Dr. Stephen Raverty, IOF adjunct professor and veterinary pathologist with the B.C. Ministry of Agriculture and Food. “There are many potential causes for their decline, pollution being one.”

One of the whales examined was ‘Luna’, an orca separated from his mother as a calf who had extensive human contact and lived in variable habitats, which may be why Luna showed a mixture of hydrocarbon contaminants.

Transient killer whales. Photo: Josh McInnes

Ultimately, humans need to reduce and eventually eliminate fossil fuel consumption to help combat climate change and conserve marine biodiversity, said Dr. Alava. “This would also serve to bolster the resilience and health of marine ecosystems, benefiting communities that rely on them such as coastal First Nations peoples as well as future generations.”

Tags: biology, British Columbia, contaminants, faculty, IOF Research Associates, Juan Jose Alava, killer whales, OPRU, orca, Pacific Ocean, pollution, whales

PICES Symposium brought together science from all around the world

We are well into the United Nations’ Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, and a symposium held by the North Pacific Marine Science Organization (PICES) brought scientists from all around the world to Seattle, Washington in late October took a look at how far we have come and how far we still have to go.

Several members from the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries presented at the symposium with the IOF’s own Anna McLaskey, who won the best oral presentation in the Biological Oceanography Committee section.

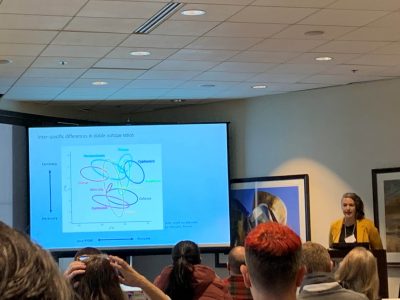

Dr. Anna McLaskey presents at PICES

Zooplankton are critical to their ecosystems for many reasons, one being that they are vital prey to many marine animals, including being the sole food source for the gigantic baleen whale. These tiny organisms also eat much of the carbon dioxide fixed by phytoplankton, causing the carbon dioxide to sink to the seabed, taking it out of our atmosphere. McLaskey’s work complements an ongoing time series project maintained at the same location in British Columbia by the Hakai Institute, and was done in collaboration with Fisheries and Oceans Canada. It involved the work of many members of the Pelagic Ecosystems Lab.

Sustainable seas and healthy ecosystems truly does take a village, and the PICES Symposium focused on connecting scientists and communities together to foster ideas for a healthy future. The organization itself was established in 1992 with present member states being Canada, Japan, People’s Republic of China, Republic of Korea, the Russian Federation, and the United States of America.

Jacob Lerner discusses his poster with an attendee

“Attending PICES was a great experience and the first time I presented my postdoctoral work in person,” said McLaskey. “In addition to my talk and being able to discuss the role of diverse prey sources with other zooplankton ecologists, a highlight of the conference for me was the workshop our group led on developing a conceptual framework to investigate and address urban impacts in coastal seas.”

The symposium focused on climate change, fisheries and ecosystem-based management, along with the social, ecological and environmental dynamics of marine systems, coastal communities and traditional ecological knowledge. The priority was to engage with one another and learn from different pools of knowledge, all united by the common goal of saving our oceans.

IOF attendees also included Dr. Brian Hunt, Jacob Lerner, Dilan Sunthareswaran, Sadie Lye, and Dr. Loïc Jacquemot from the Pelagic Ecosystems Lab; Dr. Juan Jose Alava, Dr. Zeinab Zoveidadianpour, and Kiah Lee from the Ocean Pollution Research Unit, as well as Dana Price who is cross appointed in OPRU and the Marine Mammal Research Unit, and IOF Adjunct professor, Dr. Stephen Raverty; Aleah Wong from the Changing Ocean Research Unit; and, Dr. Szymon Surma from the Marine Zooplankton and Micronekton Laboratory.

IOF students Sadie Lye and Dilan Sunthareswaran

Jacquemot’s current project focuses on using eDNA to map fish distribution in British Columbia’s fjords, and the symposium presented several opportunities to integrate new knowledge into his coming research. The symposium also allowed researchers to expand their topics of interest, with different projects taking center field, including one on European green crab invasion and ecosystem-based management exploration with Indigenous communities, NGOs, and government agencies.

PICES 2024 will be held on October 26th, 2024 in Honolulu, USA. The topic will be “The FUTURE of PICES: Science for Sustainability in 2030.”

Photos provided by Dr. Brian Hunt.

Tags: Anna McLaskey, Brian Hunt, CORU, IOF postdoctoral fellows, IOF Research Associates, Juan Jose Alava, Loïc Jacquemot, Marine Zooplankton and Micronekton Laboratory, MMRU, OPRU, Pelagic Ecosystems Lab, PICES, Szymon Surma

All-woman crew of marine scientists rowing 5,000 km non-stop for ocean conservation

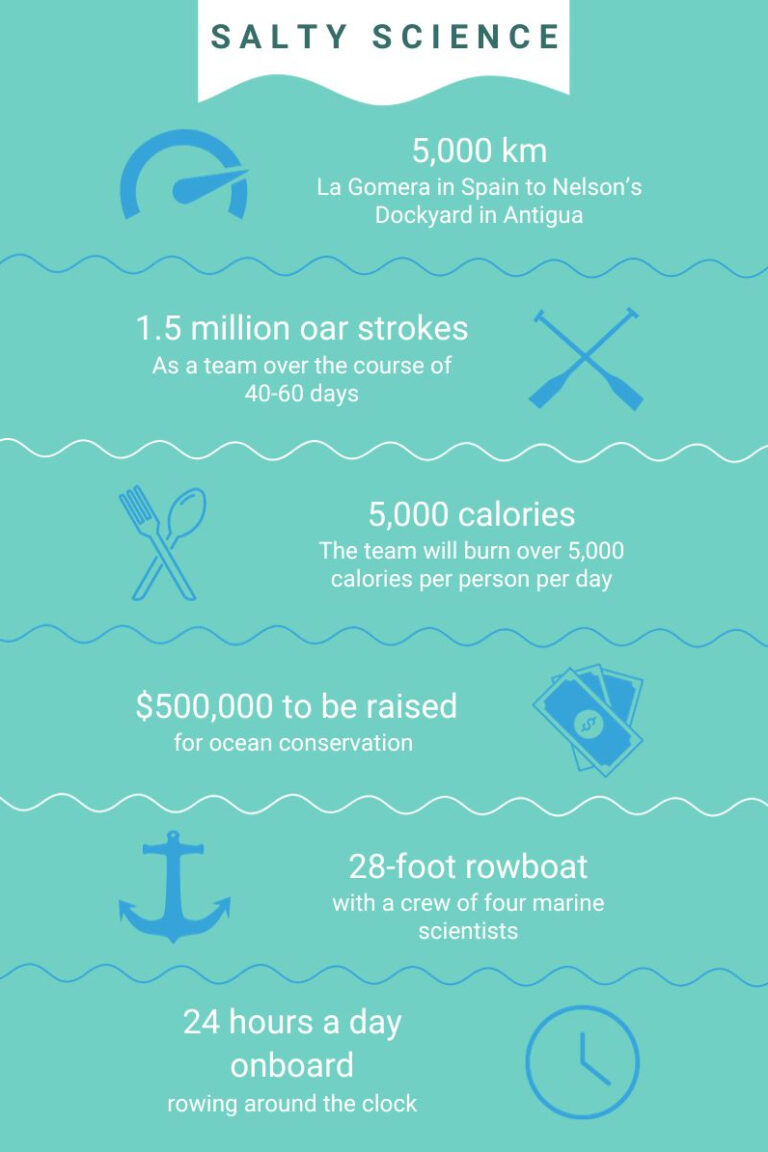

Four marine scientists are rowing 5,000 kilometres across the Atlantic to raise half a million dollars for ocean conservation.

The all-woman ‘Salty Science’ crew is taking part in the World’s Toughest Row – Atlantic 2023, where teams row without stopping and without support from San Sebastian de La Gomera in The Canary Islands to Nelson’s Dockyard in Antigua. They’ll set out on Dec. 12, weather dependent, and the voyage can take anywhere from 40 to 55 days depending on factors such as weather, the crew’s physical state and more.

They’ll take it in two-person shifts, sleeping two hours before taking the oars again for two hours, and spending 24 hours a day on the 28-foot rowboat. That means eating, sleeping and rowing in all weather—and they’ve got a bucket onboard for bathroom breaks.

“We’re feeling ready. While there are a lot of nerves and buildup, we had a good time this summer training every day in Florida for two months. We have been prepping for nearly three years at this point,” said Salty Science member Lauren Shea, a master’s student in the UBC Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries.

Her crewmates are another B.C. resident, Dr. Isabelle Côté, professor of marine biology at Simon Fraser University, as well as Dr. Côté’s former PhD student Dr. Chantale Bégin, now a professor at the University of South Florida, and Noelle Helder, Shea’s friend from undergraduate studies in Florida now working for the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“We are four women, four marine biologists, three academic generations, and we are very aware that we are acting as role models,” said Dr. Côté. “We want girls who are interested in marine biology to know that anything is possible.”

The team aims to raise USD$500,000 for marine science and conservation through three organizations: GreenWave, focused on sustainable seafood production; Shellback Expeditions, which supports marine research, conservation and education in the eastern Caribbean; and the Bamfield Marine Science Centre, which will use the team’s funds to create a scholarship for students of underrepresented minorities to help train the next generation of marine conservationists.

The crew will take more than 1.5 million oar strokes, requiring they eat at least 4,000 calories a day. Their personal belongings are limited to one 40-litre dry bag not due to weight limitations, but space, as the boat is packed stem to stern with food. They’ll even be rowing on Christmas Day, when they’ll share small gifts, and when, the team has agreed, Christmas tunes will be allowed onboard.

It will be an arduous trip, aside from the sheer physical requirements. While the team are experienced on the water, with Shea having served as chief mate aboard a sailing school ship in Antigua, they will be self-reliant when at sea, carrying three satellite phones, emergency beacons, a medical kit and handheld radios. And then there’s the weather.

“The boat is self-righting, so if it capsizes it will roll back over. Every team prepares to capsize at some point and you can deploy various tools to slow yourself down and decrease this risk, but really it comes down to preparing for different emergency scenarios and working together when issues occur,” said Shea.

“It feels a lot more real now. It’s very exciting, and every time I spend time with my team I’m that much more excited, because they’re a pretty remarkable group of people.”

Follow Salty Science during the race via this tracking app and clicking “Add Race” and typing “World’s Toughest Row – Atlantic 2023”, or via their Instagram account. Find out more on their website.

Your local sea snail might not make it in warmer oceans – but oysters will

Nucella lamellosa or frilled dogwinkles. Photo credit: Dr. Christopher Harley

Strait of Georgia hotspot

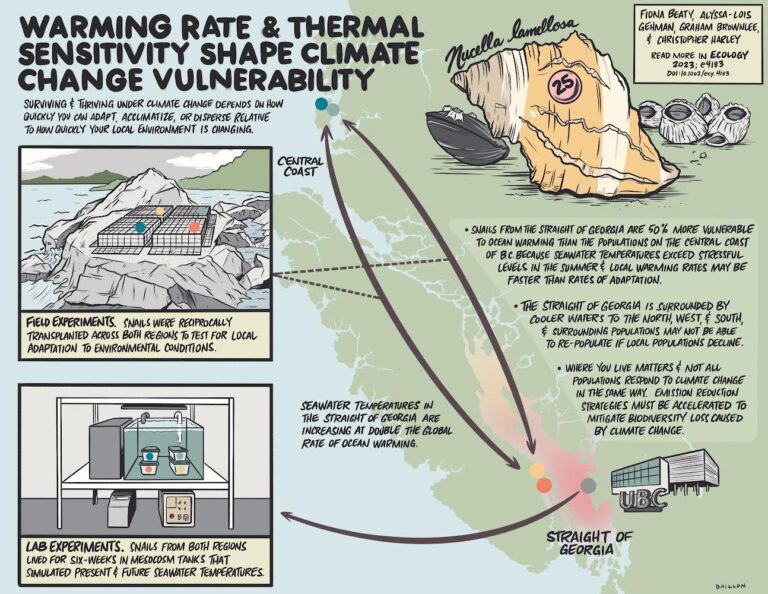

To figure out how location affects vulnerability to a changing climate, UBC zoology researchers Drs. Fiona Beaty and Chris Harley collected marine snails from the Strait of Georgia, a potential hot spot of climate risk, and the Central Coast, where waters are cooler and warming more slowly.

They monitored snails in the lab, in water heated to current and future projected sea temperatures, and in the field along shorelines.

Credit: Rush Dhillon

Movement and snails don’t go together

They found Strait of Georgia snails were 50 per cent more vulnerable to ocean warming, experiencing current seawater temperatures much closer to the upper limits of what they can tolerate than snails on the Central Coast. Indeed, up to a third more snails perished when kept on the Strait shoreline over summer than those kept on the Central Coast.

“These creatures are already experiencing temperatures beyond their comfort zone in the Strait, and they’re unlikely to keep up with warming oceans because they can’t move very far,” says Dr. Beaty, who completed the research during her PhD at UBC.

She says the work highlights that climate risk can be tied to location, even for people. If a species can’t move from an environment that is changing faster than the species can adapt, it could be in trouble.

Oysters, anchovies and whales, oh my!

The Strait could represent a dead zone in the species’ future. Meanwhile, species that will survive in a warmer future are likely those more tolerant of heat with shorter life spans, such as oysters and northern anchovy, as well as those that feed on them, such as whales.

Tags: British Columbia, Christopher Harley, climate change, faculty, Fiona Beaty, oysters, sea snails, Strait of Georgia, whales

UN climate conference should not be ‘business as usual’, say climate experts

Photo by United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change on Flickr

We spoke to four experts including current and former COP delegates to ask what the world, and Canada, needs to see come out of the conference, which will be held from Nov. 30 to Dec. 12 in Dubai.

Dr. William Cheung: The oceans must be part of the discussions

Dr. Cheung is a professor and the director of the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, a UBC COP 28 delegate and co-author of the IPCC 2023 report.

The oceans must be considered part of the discussions—they host a vast diversity of life, provide renewable energy through offshore windfarms, feed or employ a good portion of the world, serve as carbon sinks and offer a potential low-carbon pantry and economy through sustainable fishing and aquaculture.

Even if the world successfully limits global warming to 1.5 C, tropical areas, small islands, and developing states will continue to see a substantial decrease in catches and seafood availability, as well as sea level rise in the near term. We need to see the loss and damages fund used to support these actors.

Not achieving the warming limit doesn’t mean we should give up. Every degree of warming avoided helps. This requires further emissions cuts than those to which countries have already committed. Making meaningful progress in this conference is very important for addressing other global challenges including biodiversity conservation and food security.

Dr. Kathryn Harrison: Countries need to up their game

Dr. Harrison is a professor in the department of political science and a UBC COP 26 delegate.

The world isn’t on track to meet the Paris Agreement goal to limit warming to 1.5 to 2 C, and so, the most fundamental thing we need is greater ambition to reduce emissions, both in terms of national targets and domestic policies to meet them.

Wealthy countries that disproportionately caused climate change must provide greater financial support to low-income countries that disproportionately suffer its impacts. I’m also hoping to see acknowledgement of the need to phase out both consumption and production of fossil fuels.

Canada must demonstrate our word can be trusted by implementing policies needed to meet our targets, and acknowledging the need to wind down fossil fuel production. And Canada can lead in committing greater climate finance for developing countries

It’s easy to be cynical about UN climate conferences, but I’m stubbornly hopeful, because I have never been surrounded by so many people deeply committed to eliminating climate change.

Fabiola Melchior: Strengthening youth participation

Fabiola Melchior is a master’s student in Interdisciplinary Graduate Studies at UBC Okanagan, a COP 28 delegate and a climate activist.

I hope to see the parties strengthen meaningful youth participation at key decision-making events, which is crucial not only because youth are at the forefront of climate justice organizing in their communities, but especially because we continually confront the roots of capitalist and colonial structures that have led to the climate crisis. This could include the institutionalization of the Youth Climate Champion within the COP Presidency.

Going into this conference, we need to amplify calls for the implementation of a robust conflict-of-interests policy within the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. This would require the parties to maintain separation from corporate entities and limit sponsorships by polluting entities that may impact the focus, progress and outcomes of COPs. Last year 636 representatives of oil and gas industries attended COP, outnumbering any one delegation of frontline communities. It is time to take action, and kick big polluters out.

Temitope Onifade: Tackle renewable energy technologies

Temitope Onifade is an affiliated research scholar in the Peter A. Allard School of Law and a UBC COP 26 delegate.

I’d like to see countries address the management of renewable energy technologies, the most widely accepted alternative to fossil fuels. These technologies require diverse minerals, metals and other materials. Efforts to find these, such as deep-sea mining, create social and environmental challenges. COP 28 should create a framework to address such implications, which can then be implemented with partners such as the International Renewable Energy Agency.

COP 28 should not be business as usual: governments, heavily lobbied by businesses, negotiating technology and market-based systems. We have done this for decades, but it has not worked. Rather, governments should be promoting the solutions that work while empowering the countries and communities that are disproportionately impacted by not only climate change but also the solutions. They should listen to what such countries and communities think about the best ways to deal with those impacts, not what powerful industries tell them.

For more delegates, and other UBC experts, available to comment on the conference, the 2023 UNEP Emissions Gap report, and other climate-related topics, click here.

Tags: climate change, COP28, faculty, international trade, William Cheung

Diving, snacking, laying eggs! What do different hemoglobin levels mean for gentoo penguins?

For gentoo penguins, hemoglobin levels in the blood are vital for efficient diving and foraging—which in turn could impact breeding success

© Sarah McComb-Turbitt

The birth dates, and chances for survival, of these chicks are dependent on when their parents lay eggs — a factor reliant on the adults being able to forage and feed enough to have the energy to breed. A recent study published in the Marine Ecology Progress Series investigated if diving efficiency — which impacts the type and amount of food foraged — is associated with markers of oxygen storage and carrying capacities (aerobic capacities). The study then looked at if these markers are associated with pre-breeding foraging efforts and the penguins’ breeding statuses.

“We were interested in understanding how diving capacity — specifically how long gentoo penguins can stay at the bottom — is related to their aerobic condition,” said Marie Auger-Méthé, principal investigator and associate professor at the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries. “Diving deep takes time and energy, and it’s useful only if the penguin can search and catch food at the bottom. We showed that penguins with higher aerobic capacities can spend more of their dive at depth than other penguins while still taking the same amount of time to recover.”

Diving is the key to these birds’ survival. While only 30 inches tall and 15 pounds, gentoo penguins can swim up to 22 miles an hour, the fastest of any diving bird. They exhibit a range of diving behaviours, preferring to shallow dive to preserve energy while their deep dives can reach depths of over 200 metres. They eat different types of squid, fish and krill, with larger, more energy-rich prey being found closer to the ocean floor.

While foraging is important for the survival and wellbeing of many animals, gentoo penguins have to increase their time on land to bond with their mate and maintain nesting sites before laying eggs. This means that successful food foraging during the pre-breeding season is absolutely essential for these birds as they prepare to expend energy to defend their nests and lay eggs. A penguin with plenty to eat will lay eggs sooner compared to unlucky counterparts, creating a higher survival rate for their own offspring. Gentoo penguins can lay up to two eggs per year, but some will skip a year and forage, choosing to replenish their health so they are able to better raise chicks in the future.

© Sarah McComb-Turbitt

So, what exactly impacts the gentoo penguin’s ability to dive and find food before breeding?

During a dive, the penguin’s effort can be measured by the trip duration, total time spent at sea and the vertical (dive) distance traveled. With larger prey found at the bottom, penguins that can dive deeper and longer have a better chance of feeding sufficiently. Hemoglobin (Hb), the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen to all parts of the body, is a key factor for diving penguins. Penguins with higher hemoglobin levels dive more frequently at deeper depths (more than 140 metres) and can spend more time at these extraordinary depths. These penguins also don’t need to spend more time replenishing their oxygen stores, which means they can forage for food much more efficiently. They are able to find more food — and also better and rarer food — compared to other penguins, which reduces competition and saves energy.

Hematocrit (Hct) is the percentage of red blood cells in blood. It can also be a factor for diving capacities, as sometimes, a higher percentage of hematocrit may mean a higher amount of hemoglobin, which means more oxygen carrying capacities. However, a higher hematocrit doesn’t necessarily mean a better dive — having more red blood cells thickens blood, creating lower circulation and making the heart work harder to circulate the blood.

© Sarah McComb-Turbitt

“These kinds of studies are really important because while most research still tries to describe what a typical individual of a species does, we know that individuals vary drastically in their conditions, behaviour and reproduction,” said Auger-Méthé. “In some cases, there may not be a typical individual that represents the majority in a population. These differences can have a large effect on their resilience to human stressors, as some individuals may be hit harder than others.”

With gentoo penguins, human stressors can mean anything from climate change, fishing and tourism to pollution, invasive species and human development.

“Pollution from shipping, oil spills and other maritime activities introduce contaminants that penguins ingest and carry,” said McComb-Turbitt. “Commercial fishing, particularly for squid and fish, is also a significant industry in the Falkland Islands. Overfishing could impact the food availability, and consequently, a penguin’s survival and ability to reproduce.” Additionally, different types of fisheries can have varying effects on the penguins. Inshore overfishing may disproportionally impact penguins with low aerobic capacity, as they would not be able to reach fish in offshore waters.

These penguins, however, are resilient little creatures who use their flexible diets and diving capacities to quickly adapt to changes in their environments. The Falkland gentoo penguins are genetically different to their relatives in Antarctica, making future studies vital to understanding more about these fascinating animals.

Diving efficiency at depth and pre-breeding foraging effort increase with haemoglobin levels in gentoo penguins published in the Marine Ecology Progress Series

© Sarah McComb-Turbitt

Tags: biology, birds, energetics, faculty, Falkland Islands, foraging, hemoglobin, IOF alumni, IOF students, Marie Auger-Methe, penguins, reproduction, seabirds

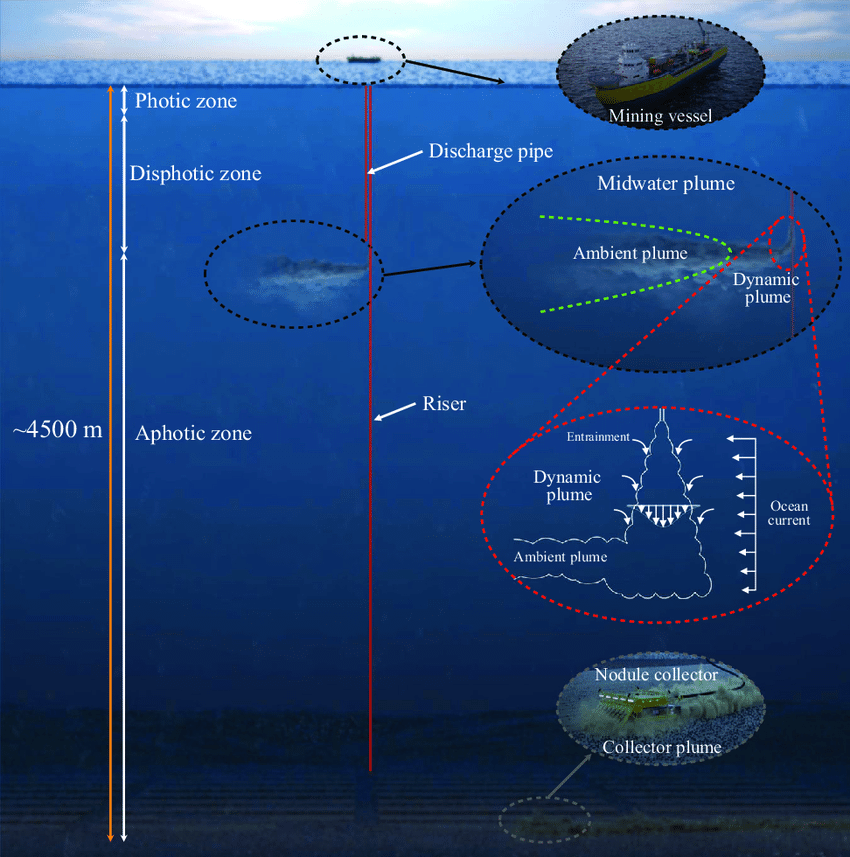

“Who stands to benefit?” To engage in deep-sea mining or not. Not, say international scientists

Private companies may secure short-term profit, but deep sea mining comes at a major cost for humanity.

Deep sea mining boat, image compiled by Lubna

Deep sea mining will produce far too few benefits for the harm it will cause. That is the result of an analysis by marine scientists and policy experts from around the globe, led by Dr. Rashid Sumaila from the University of British Columbia.

While advocates of deep-sea mining say that the investment is needed to provide the metals needed for electric car batteries and other electronic infrastructure for a carbon neutral economy, opponents point to the irreparable damage that it would have on the environment, including delicate habitats on the seafloor, and the detrimental effect it will have on developing nations, including those that may directly benefit from deep sea mining in their area.

The researchers looked at the cost and benefits for private mining companies and their investors, developing countries, including those who could directly benefit from deep sea mining in their area, countries engaged in terrestrial mining, and ‘nature’ itself, and found that while there would be some short-term private company profits, over the longer term the benefits would dwindle. Most particularly for developing nations, the natural world and humanity as a whole.

“On a purely economic level, capital and operational costs would be very high. Approximately US$ 4-6 billion. Projected revenues are estimated to US$ 9-11 billion, however that is over a thirty-year period,” said Dr. Rashid Sumaila, lead author and professor in UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF) and the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs. “Add to that the operational costs of refining the polymetallic nodules mined, at best the annual profit would be in the region of US$1.2 billion. Investors may like those numbers; however, they are also likely to have those profits chipped away at by both litigation and business model risks, as surges in climate change and biodiversity impacts take their toll, along with foreseeable litigation from aggrieved countries, communities and other stakeholders impacted by deep sea mining.”

Developing countries, including those who are attracted to deep sea mining for its potential to generate economic benefits such as tax revenues and jobs, will gain little, according to the commentary. “Sponsoring member states will likely benefit from a corporate tax payment of 25 per cent – approximately US$3 billion. However, it will be divided amongst the states over the same 30-year contract period,” said Dr. Lubna Alam, co-author and research scholar at the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries. “It will deliver pittance to those countries.”

Photo by Carlos Muñoz-Royo

The ecological damage would be even worse. “We know so little about our oceans, and even less about the seafloor itself. The irreversible damage that it is going to do to very delicate ecosystems is horrific,” Sumaila said. For instance, a single mining operation could release up to 80 km³ of sediment plume into the ocean every day, spreading to an area of up to 24,000 km² in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone alone. This plume is capable of reducing light penetration and water oxygenation while at the same time dispersing toxins and radioactivity.

Dr. Sumaila does point to some international movement on this issue. The International Seabed Authority (ISA), an intergovernmental organization established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to regulate the exploration of minerals found on the international seafloor, began its most recent round of meeting on the subject on October 30th, and already 23 countries, including many small island developing states who would be directly affected by deep-sea mining, as well as large developed countries including Canada and the United Kingdom have asked for a moratorium, or ban on deep sea mining.

“At the time when safeguarding biodiversity and ecosystems is paramount, this analysis of deep-sea mining’s economics is timely,” said Dona Bertarelli, philanthropist and ocean advocate who funded this research. “Highlighting short-term gains for a few, but enduring costs for coastal communities and states most reliant on a thriving, healthy ocean. I hope this study will prompt International Seabed Authority member states to stop and reflect.”

“The minerals on the international seafloor are humanity’s common heritage,” said Dr. Rashid Sumaila, lead author and professor in UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries. “However, our analysis shows that while deep sea mining may provide short-term profits for mining companies and marginal benefits to developing countries, long term benefits will be minimal due to anticipated business model and litigation risks, public opposition, and competition from land-based mining. In fact, this action could come with dire, irreparable loss to nature and humanity as a whole.”

Twenty-three countries who have joined the ‘Global Tide of Opposition to Deep Sea Mining’

2022: Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Fiji, France, FSM, Germany, New Zealand, Panama, Paulau, Samoa, Spain

2023: Brazil, Canada, Dominican Republic, Finland, Ireland, Monaco, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Vanuatu

To engage in deep-sea mining or not to engage: what do full net cost analyses tell us? was published in Nature

Tags: contaminants, deep sea mining, faculty, International Seabed Authority Assembly (ISA), mineral deposits, mining, ocean ecology, pollution, Rashid Sumaila, sea floor, UNCLOS