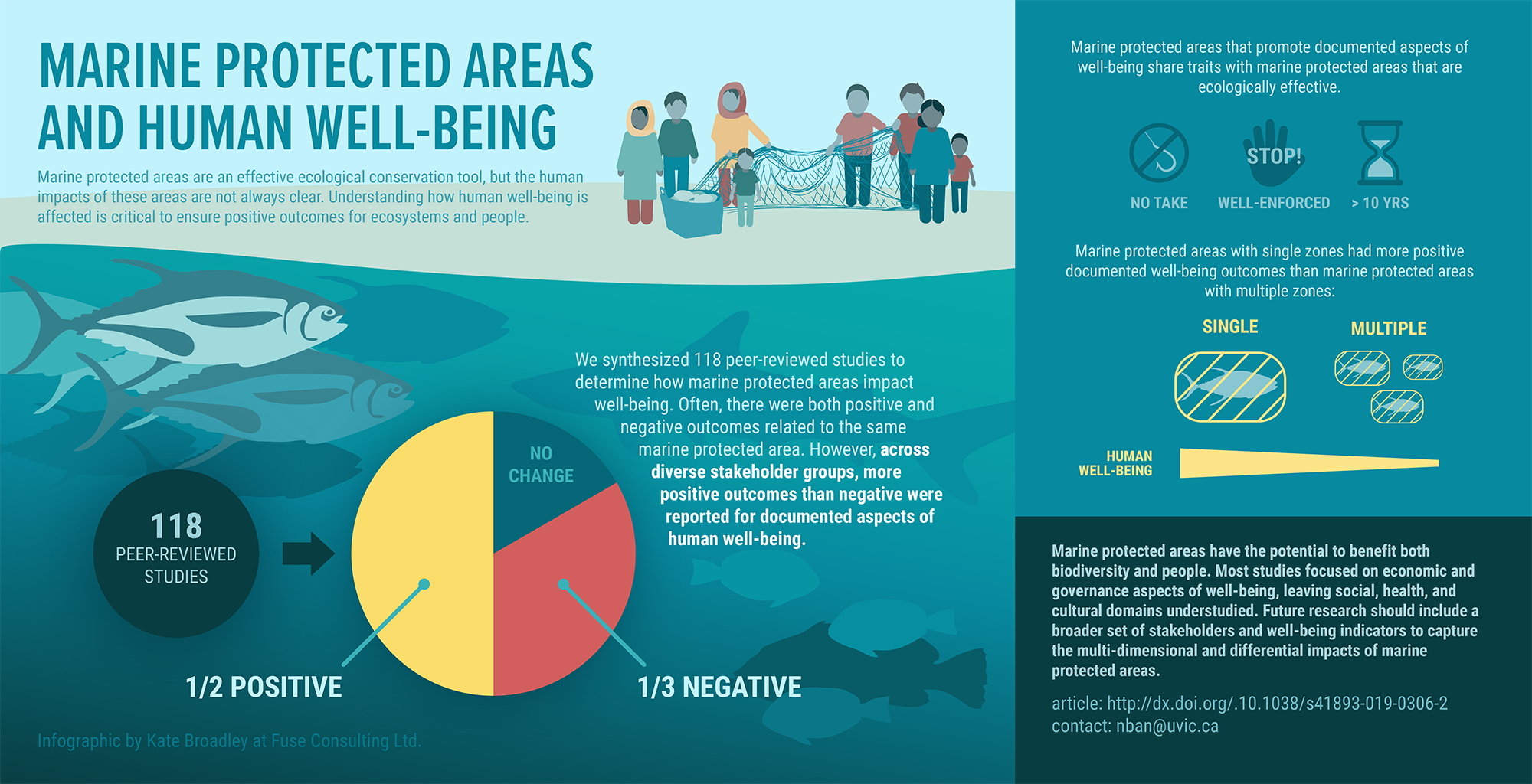

A new study finds that marine protected areas (MPAs) have the potential to help both the environment and people’s well-being, with positive and negative impacts often occurring at the same time, shedding light on a traditionally understudied area.

The study investigated how different aspects of human well-being are affected by the use of MPAs, marine regions that are legally protected and managed in order to protect natural resources and prevent biodiversity declines. While research shows that MPAs are effective for conservation, their impact on human well-being is less known.

“We found that marine protected areas often lead to improvements in human well-being,” said Dr. Nathan Bennett, a co-author of the study and Research Associate with the OceanCanada Partnership at the University of British Columbia’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries and at the Université Côte d’Azur. “Sometimes, however, MPAs can also produce negative consequences for local people. It is important to understand why these different outcomes are occurring.”

Reviewing a wide range of global research, the researchers examined how MPAs affected the social, health, culture, economic, governance and environmental domains of people’s well-being. This helped them uncover answers like how human well-being is usually defined and studied, which factors influence whether MPAs have positive or negative effects on well-being, and whether well-being outcomes vary when different MPA stakeholders are involved.

The researchers found that, overall, MPAs have more positive than negative outcomes for human well-being across diverse stakeholder groups, suggesting they can provide benefits for biodiversity as well as people. However, while the researchers found that some attributes of MPAs benefit both ecology and people’s well-being – like MPAs that are no-take, well-enforced and old – small MPAs had more positive well-being outcomes, while large MPAs are shown to be more ecologically effective. This shows that certain characteristics of MPA design and management can benefit both ecology and people’s well-being, but other characteristics require trade-offs between the two.

Graphic provided with permission from Dr. Natalie Ban, University of Victoria

“While we found more positive than negative human well-being outcomes of MPAs, it is interesting that commonly both can be found in the same MPA,“ said Dr. Natalie Ban, the study’s lead author and co-lead of the Pacific Working Group of the OceanCanada Partnership. She is an Associate Professor in the School of Environmental Studies at the University of Victoria and a UBC alumnus.

Whether MPAs led to positive or negative well-being outcomes was influenced by the direct effects of MPA governance processes or management actions, and by indirect effects from changes in the ecosystem. Direct effects included community involvement in management and conflicts arising during MPA planning processes, while indirect effects were generally due to recovering marine ecosystems like increased catch and income from resources.

“Studies that drill more into how to design MPAs that support both nature and people are crucial. This will help produce MPAs that are doubly beneficial,” said Dr. Rashid Sumaila, Director of the Fisheries Economics Research Unit, and a professor at UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries and the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs. Sumaila is also the Director of the OceanCanada Partnership, which was a co-sponsor of the research.

The researchers found that studies mostly focused on how MPAs impact people’s economic well-being, such as their income or fishing catches, while giving much less attention to people’s social, health and cultural well-being. This can become an issue if these domains – which are harder to quantify and understudied, but are important for people’s acceptance of and compliance with MPAs – disappear from decision-making situations when not measured by researchers.

“We have an opportunity in Canada to design world-class networks of marine protected areas that not only conserve biodiversity but also account for the rights, needs and well-being of coastal communities,” said Bennett. “Using rigorous social science to understand and manage the social impacts of conservation can help to ensure that local people will support conservation.”

The study “Well-being outcomes of marine protected areas” was published in the journal Nature Sustainability.

Tags: biodiversity, faculty, FERU, IOF alumni, IOF Research Associates, Marine protected areas, Nathan Bennett, OceanCanada, Rashid Sumaila, Research