To understand our present and envision the future, we must also understand our past.

These two new Fisheries Centre Research Reports will help us understand the overpowering changes that colonial settlement and development has had on the marine ecosystems surrounding the Lower Mainland area of British Columbia. Today, we are seeing these accrued impacts in severe, long-term effects on ecosystems and physical environments, and on the lifeways, cultural practices, and traditional diets of Indigenous communities, particularly Tsleil-Waututh Nation, who have lived in this coastal area since time immemorial.

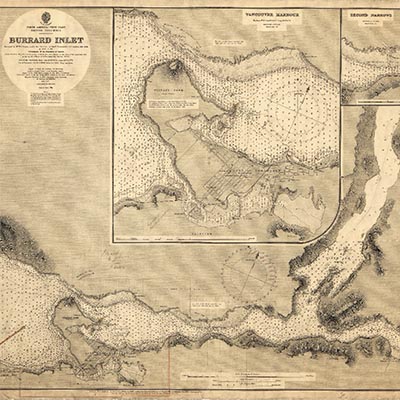

The first, Reconstructing the pre-contact shoreline of Burrard Inlet (British Columbia, Canada) to quantify cumulative intertidal and subtidal area change from 1792 to 2020, looks at how colonial development has severely altered landscapes, including in Tsleil-Waututh Nation’s (TWN) territory, centred on present-day Burrard Inlet, BC, where urban and industrial expansion has modified the inlet’s shoreline for well over a century. These shoreline changes have degraded the ecosystem and affect TWN in innumerable ways, but non-Indigenous communities have not considered the impacts of total shoreline change in detail, and generally accept shoreline changes that have occurred since European contact as the “baseline” condition of Burrard Inlet. In this study, the authors used multiple lines of evidence to reconstruct the shoreline of Burrard Inlet as it existed prior to European contact in 1792 and quantified the spatial extent of intertidal and subtidal area change in the inlet from 1792 to 2020. The results demonstrate that, across Burrard Inlet, a total of 1,214 ha of intertidal and subtidal areas have been lost to development and change, including 55% (945 ha) of the inlet’s intertidal areas. The most severe shoreline alteration occurred in False Creek and the Inner Harbour, including loss and elimination of ecologically productive and culturally important intertidal habitats at False Creek Flats (>99% intertidal area lost), the Capilano River Estuary (80% intertidal area lost), and the Seymour-Lynn Estuary (56% intertidal area lost). This shoreline loss has fundamental consequences to Burrard Inlet’s ecosystem and TWN’s ability to exercise constitutionally-protected rights. Further, this work demonstrates that any potential future shoreline loss must consider historical shoreline change and cumulative effects in Burrard Inlet.

The first, Reconstructing the pre-contact shoreline of Burrard Inlet (British Columbia, Canada) to quantify cumulative intertidal and subtidal area change from 1792 to 2020, looks at how colonial development has severely altered landscapes, including in Tsleil-Waututh Nation’s (TWN) territory, centred on present-day Burrard Inlet, BC, where urban and industrial expansion has modified the inlet’s shoreline for well over a century. These shoreline changes have degraded the ecosystem and affect TWN in innumerable ways, but non-Indigenous communities have not considered the impacts of total shoreline change in detail, and generally accept shoreline changes that have occurred since European contact as the “baseline” condition of Burrard Inlet. In this study, the authors used multiple lines of evidence to reconstruct the shoreline of Burrard Inlet as it existed prior to European contact in 1792 and quantified the spatial extent of intertidal and subtidal area change in the inlet from 1792 to 2020. The results demonstrate that, across Burrard Inlet, a total of 1,214 ha of intertidal and subtidal areas have been lost to development and change, including 55% (945 ha) of the inlet’s intertidal areas. The most severe shoreline alteration occurred in False Creek and the Inner Harbour, including loss and elimination of ecologically productive and culturally important intertidal habitats at False Creek Flats (>99% intertidal area lost), the Capilano River Estuary (80% intertidal area lost), and the Seymour-Lynn Estuary (56% intertidal area lost). This shoreline loss has fundamental consequences to Burrard Inlet’s ecosystem and TWN’s ability to exercise constitutionally-protected rights. Further, this work demonstrates that any potential future shoreline loss must consider historical shoreline change and cumulative effects in Burrard Inlet.

The second, Historical Ecology in Burrard Inlet: Summary of Historic, Oral History, Ethnographic, and Traditional Use Information, looks at the profound changes, undergone by the marine ecosystems surrounding the Lower Mainland area of British Columbia, resulting from poor fishery practices, pollution, and habitat destruction associated with the development of a large urban centre and Canada’s busiest port. To gain a better understanding of pre-contact ecological conditions in Burrard Inlet and surrounding waters, and to assess the scope and magnitude of negative impacts to key species, an extensive review of historic, archival, ethnographic, Traditional Use Studies (TUS), and other relevant materials was undertaken. This body of information provides unique insight into the past abundance of species across the study area and identifies key periods of change. Almost all of the taxa identified in the literature review displayed evidence for decreased abundance in modern compared to early historic times, and in many cases, this decrease was profound. Specifically, this review identified major population reductions of herring, smelt, eulachon, salmon, sturgeon, groundfish, clams, crab, whales, and waterfowl. For all taxa reviewed, save for cod, where the data make it possible to estimate, this review indicates that estimated current population abundances for focal species ranges from less than 1% to 50% of their mid-19th century and pre-contact levels.

The second, Historical Ecology in Burrard Inlet: Summary of Historic, Oral History, Ethnographic, and Traditional Use Information, looks at the profound changes, undergone by the marine ecosystems surrounding the Lower Mainland area of British Columbia, resulting from poor fishery practices, pollution, and habitat destruction associated with the development of a large urban centre and Canada’s busiest port. To gain a better understanding of pre-contact ecological conditions in Burrard Inlet and surrounding waters, and to assess the scope and magnitude of negative impacts to key species, an extensive review of historic, archival, ethnographic, Traditional Use Studies (TUS), and other relevant materials was undertaken. This body of information provides unique insight into the past abundance of species across the study area and identifies key periods of change. Almost all of the taxa identified in the literature review displayed evidence for decreased abundance in modern compared to early historic times, and in many cases, this decrease was profound. Specifically, this review identified major population reductions of herring, smelt, eulachon, salmon, sturgeon, groundfish, clams, crab, whales, and waterfowl. For all taxa reviewed, save for cod, where the data make it possible to estimate, this review indicates that estimated current population abundances for focal species ranges from less than 1% to 50% of their mid-19th century and pre-contact levels.

We salute the authors of these Fisheries Centre Research Reports for their determination in helping us understand the shifting baselines in the Burrard Inlet and the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, and how they have challenged the ecosystems and peoples who live in this coastal area.

You can find both Reports here.

Tags: Aboriginal fisheries, birds, British Columbia, coastline, FCRR, fish, fish stocks, fishing practices, Indigenous fisheries, IOF students, ocean ecology, Publications, Research, Tsleil-Waututh Nation, Villy Christensen, whales