Quadra Island summer sampling trip – July 2019

The HCI food webs field team: (l to r) Jessica Schaub, Caterina Giner, Rosie Savage, Vera Tai, Brian Hunt, Jackie Maud, Lauren Portner, Anna McLaskey, Colleen Kellogg

The connections between the animals that form the base of marine food webs are still largely unknown. This critical knowledge gap is an area that the Hakai Coastal Initiative Marine Food Webs Working Group (FWWG) specifically aims to fill. Doing so would improve our understanding of how the plankton and microbes that ultimately supports the majority of marine life would respond to climate change. Spearheaded by Dr Brian Hunt (Director, UBC

Pelagic Ecosystems Lab), Dr. Colleen Kellogg (

Hakai Institute) and Dr Vera Tai (

Western University) the FWWG is using a variety of cutting-edge genomic techniques to assess the community structure and interactions of marine pelagic species.

Over the summer of 2019 their team of postdoctoral fellows, students, volunteers, and a technician headed to the Hakai Institute’s field station on Quadra Island for an intense ten (10) days of sampling. The team was focused on collecting data on the day/night behaviour of bacteria, protists, zooplankton, and parasites in the Strait of Georgia. It is relatively rare to get night samples and this data will help understanding which species are in the water column at different times of the day, and what they are eating whilst they are there. To do so, the team collected samples at different depths, from surface to 200m three times per day (morning, afternoon, night) for a total of four days. The team will process the samples once they return to UBC; typically, this involves extracting and sequencing the DNA from each sample to characterize the microbial and zooplankton community. This technique (called ‘metabarcoding’) will also be used during molecular gut content analyses to identify what the zooplankton are eating.

Caterina Giner collecting DNA

To characterize the microbial components of the food web (i.e., bacteria and protists) Dr. Caterina R. Giner and Dr. Colleen Kellogg filtered several litres of seawater from every visit to the sampling site. This way they were able to collect the miniscule nano- and pico-plankton. “Bacteria and small protists are mostly lacking in morphological characteristics that allow us to identify them under the microscope. So, once in the lab, we will extract and sequence the DNA and RNA, which will tell us which microbial species are there, but also which ones are more active at the different times of the day,” said Dr. Giner.

Heading out for night sampling

The team was also interested in what these tiny organisms were doing throughout the day. Many zooplankton perform a daily migration from the depths during the day to the surface after dark. This process, called diel vertical migration (DVM), is a predator avoidance mechanism, where species hide in the depths during the day and come to the surface to feed at night when there is less chance that they might be seen by predators. Dr Jacqueline Maud (Hakai Postdoctoral Fellow, IOF), a plankton ecologist, was collecting zooplankton from varying depths during the 25 hour period to see where certain key species are and what they are eating at that depth. “Marine scientists rarely get the opportunity to sample zooplankton at night and it’s a very different landscape out there once the sun goes down and the zooplankton come to the surface” comments Jacqueline. She adds “We’re so lucky that we can use the Hakai Institute boats and equipment to collect plankton after dark, also because many jellyfish appear at the surface at night and we can find out what they’re feeding on.”

Gelatinous zooplankton are generally less well studied than other hard-bodied zooplankton. Both Dr. Maud and IOF Master’s student Jessica Schaub are hoping to change some of that. Jessica is focusing on the moon jelly Aurelia aurelia and was collecting individuals to undertake molecular gut content analysis of their stomachs.

Dr Vera Tai (Western University, Ontario) and Master’s student Rosie Savage are looking at the food web from a different perspective. Using metabarcoding they are hoping to detect zooplankton parasites from some of the dominant zooplankton species; a topic which very little is currently known about. Some parasites can be seen in and on the body of the zooplankton individuals, but these are easily missed; DNA metabarcoding can detect their occurrence.

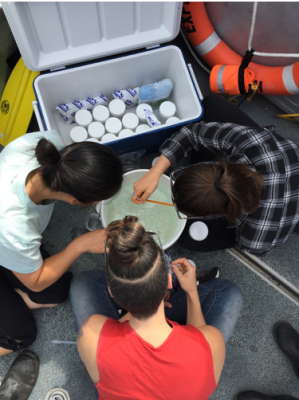

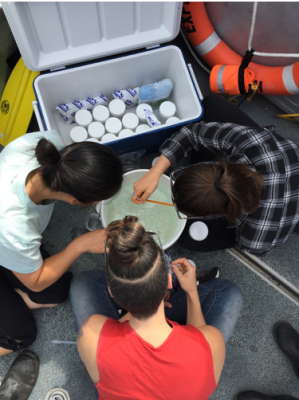

Sorting the catch

Collectively this research will unite all the new information obtained from the different components of the food web; the scientists will be able to identify the key players but also the interactions between them. Dr Hunt commented that “this work is novel in that we are trying to pull together knowledge from every component of the plankton food web and use it to inform how the Strait of Georgia ecosystem will respond to pressure like warming and ocean acidification.” By doing so this team aims to contribute to understanding of the role of plankton in the survival of salmon and herring in BC coastal waters.

Tags: Brian Hunt, faculty, food webs, Hakai Coastal Initiative, Hakai Institute, IOF postdoctoral fellows, IOF students, jellyfish, Pelagic Ecosystems Lab, plankton, Research