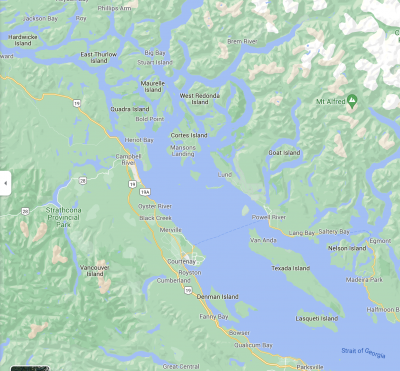

Areas of B.C.’s coastal ocean that are next-door neighbours look very different under the surface and may experience environmental stressors differently

Queen Charlotte Strait to Johnstone Strait

An ocean front, where two bodies of water with different temperatures and salt concentrations meet and mix together, cuts these areas in half. Johnstone Strait and the Discovery Islands are connected by narrow channels with rough sea floors, where the movement of some of the strongest tidal currents in the world mixes the cooler, saltier waters of Johnstone Strait and the warmer, less saline waters of the Strait of Georgia together. Viewed from above, this makes the ocean look as though it is boiling and, on either side of the point, there is a major change in properties between the two bodies of water.

Although the reasons for this divide are still not certain, a recently-published study from UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF) found that the area is even quirkier than previously thought.

“There is a really dramatic difference in the water properties between these regions that are directly connected to each other,” said Hayley Dosser, the study’s lead author and a postdoctoral fellow with UBC’s Department of Earth Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences. “Beyond just temperature and salinity differences, which have been noted before, we also found that the ratios of the nutrients that matter to phytoplankton – such as nitrate, phosphate and silicate – were very different between the regions.”

©Grant Callegari/Hakai Institute

“We see these really sharp differences, regardless of what the tides are doing, or what season we’re in, for over 70 years. The data shows this persistence,” Dosser said.

Different responses to ecosystem stressors

These differences mean that areas right next to each other will respond in unique ways to ecosystem stressors such as ocean acidification, heat waves, and ocean warming, according to Dosser.

“We spend a lot of time thinking of these areas as two clumps: Discovery Islands and the Strait of Georgia, and then Johnstone Strait and Queen Charlotte Strait,” Dosser said. “In some ways that only tells half the story. There’s so much mixing in Johnstone Strait and the Discovery islands, that they have their own weird way of reacting to stressors. The Discovery Islands, for example, are uniquely vulnerable to ocean acidification. There are so many things you have to consider even for a tiny region.”

The study found that Johnstone Strait and Queen Charlotte Strait experienced more extreme temperatures than the Strait of Georgia and Discovery Islands during the deadly 2013-2016 marine heatwave known as “The Blob.” The authors believe that the cooler, saltier northern region may be more vulnerable to heat waves because it is directly connected to the open ocean, while marine species in the Strait of Georgia, which is more sheltered from the open ocean, may dodge the worst outcomes from high temperatures.

Discovery Islands and Strait of Georgia

“Salmon can spend anywhere from one to two weeks in this stressful environment, where they experience low food availability and acidic waters,” said Brian Hunt, co-author and assistant professor at the IOF. “This is a natural phenomenon that they’ve been experiencing for millennia, but changes like increasing temperatures and heat waves will likely make it worse. If you have poor feeding conditions in the Strait of Georgia, or in Queen Charlotte Strait, then you have a double-whammy. If they starve for four weeks, they’re not in good shape.”

Understanding how environmental conditions in different ocean regions will shift due to climate change and extreme events is essential to figuring out the future of marine species, including salmon, in B.C.

“This study was a real collaboration, with the kind of data coverage and interdisciplinary expertise we need to support management of B.C.’s coastal ocean,” Dosser said. “We can’t just take measurements in one location and assume conditions will be the same in nearby locations. There may be huge differences over even small distances.”

The study “Stark Physical and Biogeochemical Differences and Implications for Ecosystem Stressors in the Northeast Pacific Coastal Ocean” by Hayley Dosser, Stephanie Waterman, Jennifer M. Jackson, Charles G. Hannah, Wiley Evans, and Brian Hunt was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans.

Tags: Brian Hunt, British Columbia, environment, Hakai Institute, heatwaves, plankton, salinity, salmon, temperatures, water