Members of the C1 and D1 pods of northern resident killer whales as they travel near Alert Bay, BC.

Photo ©UBC – Hakai Institute/K. Holmes

The research is part of a multi-year investigation, supported by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, NSERC, the Pacific Salmon Foundation, and Hakai Institute, into whether endangered southern resident killer whales are getting enough of their preferred prey, Chinook salmon, to meet their nutritional needs. The researchers used aerial drones and underwater cameras with biologgers to study their feeding behaviour, and hydrophones to measure prey availability.

We spoke to the lead investigators, Professor Andrew Trites and postdoctoral fellow Sarah Fortune, about the trip, preliminary findings, and how COVID-19 impacted their research.

This was your second summer gathering footage and data on northern and southern resident killer whales to study their feeding behaviour. What stood out to you?

Sarah Fortune: It was so amazing to be able to travel underwater with the killer whale pods. For the first time, we were able to clearly hear and see what the killer whales experience as they search for food, capture fish, and interact with each other. The suction-cupped cameras that were temporarily stuck on the resident killer whales allowed us to see and understand them in a way that no one has ever been able to do before. Some of the things we recorded will refine current understanding of how killer whales live together, hunt, share food, and communicate with one another.

Andrew Trites: Looking at the drone footage we collected on our research voyage last year, one of the things that struck us was the extent to which resident killer whales touched each other. This year we were able see this touching from their perspective. In one instance we got to see a northern resident whale calf getting its belly rubbed by its mother’s pectoral fin as they swam side by side. It was something nobody could see if they were watching killer whales from a boat. It showed us how much goes on underwater between surfacings that no one has any idea about.

You also use hydrophones to capture data on fish availability. Are there any preliminary findings you can share?

Andrew Trites: We surveyed in the North Island Waters (e.g., Johnstone Strait and Blackfish Sound) and in the Salish Sea (e.g., off of the Fraser River and along Saturna Island), and saw large salmon-sized fish in all of those feeding areas. We can’t say which areas had more salmon yet; we have to analyze more than 500 kilometres of track lines that we surveyed. However, our first impression is that there appeared to be a lot of salmon when killer whales were absent. This suggests that not seeing southern resident killer whales frequently in the Salish Sea may not be due to an absence of food for them.

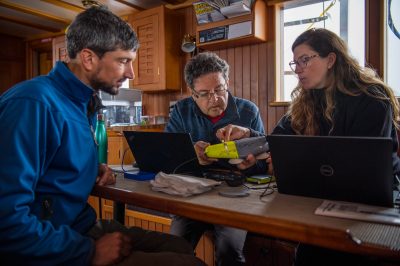

Mike deRoos (left), Andrew Trites (centre) and Sarah Fortune (right) examine the CATs suction-cup camera and data logger, and discuss programmable settings to record sound, video, depth and movements. Photo ©UBC/S. Schneider

Following killer whales while they feed while collecting hydroacoustics data to assess the presence and abundance of fish. Sarah Fortune (seated) records behavioural data, while Keith Holmes (drone pilot) prepares to record overhead behaviours, and Taryn Scarff gets ready to launch the drone.

Photo: ©UBC/A.W. Trites

This was a very challenging summer for field work. How did COVID-19 impact your trip?

Andrew Trites: The research team had to self-isolate prior to boarding our research boat, and have been in a research bubble for 30 days. It’s a long time for nine people to be locked up on a small boat. We missed walking on shore, interacting and speaking with local fishers and with other researchers, as we did last year, about what they were seeing and catching. Fortunately, the scenery changed every day, as did the marine life we encountered. With fewer eyes and boats on the water this year, we were also fortunate to receive updates on whale locations and movements from the Pacific Whale Watch Association members and from shore-based observers such as SIMRES (the Saturna Island Marine Research and Education Society) that helped us plan our days.

Sarah Fortune: We saw fewer large ships this year (particularly in the north), and had the impression that things were quieter. However, we did not notice any marked change in whale behaviour to suggest that it made a significant difference to the whales. Other researchers will undoubtedly be analysing vessel movements, ocean noise and whale presence to say something more conclusive about the impact quieter seas might have had on the whales.

Tags: Andrew Trites, British Columbia, faculty, IOF postdoctoral fellows, killer whales, Marine Mammal Research Unit, marine mammals, Research, salmon, Sarah Fortune, whales