In a special issue of Maritime Studies that explored women in fisheries management, two papers published by UBC IOF researchers investigated women’s roles in fisheries governance in two different populations: the Heiltsuk Band on Bella Bella in British Columbia, and fishers in the Danajon Banks of the Philippines.

In the paper Indigenous women respond to fisheries conflict and catalyze change in governance on Canada’s Pacific Coast, Sarah Harper, IOF PhD student and lead author, examined the roles of Heiltsuk women during a 2015 fisheries crisis, and how their unique position empowered governance changes in Pacific herring management on British Columbia’s Central Coast.

“Heiltsuk women took on key roles in terms of leadership in organizing the community and bringing the community together, and challenging the current governance system and creating change,” Harper said. She, along with the other researchers, interviewed Heiltsuk members involved in the 2015 crisis and identified important actions taken by women in the community.

Herring crest by Heiltsuk Artist Nusi (Ian) Reid, depicting Raven and a Heiltsuk noblewoman sharing a canoe surrounded by spawning female herring.

A long-time source of livelihood, herring is of significant economic, social and cultural importance for the Heiltsuk. Fisheries conflicts between the Heiltsuk and local institutions date back far before the 2015 crisis, with a history of court cases, licensing negotiations, and litigation.

From 2008 to 2013, commercial fisheries were closed due to low herring numbers on the Central Coast. Despite recommendations from First Nations to let stocks recover by leaving the fisheries closed, commercial herring fisheries were re-opened, leading to protests by the Heiltsuk and other First Nations. The opening of a commercial sac-roe fishery in 2015 culminated in a stand-off on the water, where two Heiltsuk women took actions at the forefront to protect their rights to conserve herring.

The opening of a commercial sac-roe fishery in 2015 culminated in a stand-off on the water, where two Heiltsuk women took actions at the forefront to protect their rights to conserve herring.

Shortly after, Heiltsuk members delivered an eviction notice to the local federal fisheries agency office, leading to an occupation and lock-down of the office by the elected leadership. This ultimately led to further negotiations and a new herring management plan, developed collaboratively and adopted in 2016. A year later in 2017, the Heiltsuk Nation and the Province of British Columbia signed a framework agreement for reconciliation, further sharing the power of fisheries resource governance between the two parties.

The researchers found that in the 2015 herring conflict, Heiltsuk women drew from both their traditional and contemporary roles as mothers, teachers, community and domestic managers, and political leaders who were promoting intergenerational care by defending their children, culture, and future generations.

“Drawing on this identity around care for children and future generations – and looking at other examples with respect to fisheries and environmental issues more broadly – there were examples where women drew strength from this motherhood identity,” Harper explained. “In some ways, that depoliticized the role that women took in those settings and made them more effective at negotiating and being at the forefront of those struggles.”

“Drawing on this identity around care for children and future generations – and looking at other examples with respect to fisheries and environmental issues more broadly – there were examples where women drew strength from this motherhood identity,” Harper explained.

This is consistent with many other Indigenous cultures, where women often bear the roles of mothers and caregivers, and harness this positioning in their political and environmental activism. In Heiltsuk creation stories, women are portrayed as peacemakers responsible for intertribal alliances, characteristics that featured heavily in the leadership style of women in the 2015 conflict.

While the whole community was involved in the conflict, women stood at the forefront of the negotiations and demonstrations in Vancouver. They protested at government and industry offices, and used social media to promote cohesion and the flow of information. Their ability to coordinate, organize the community, and lead informally were gendered strengths that set the framework for system-level governance transformation through harnessing social networks and building momentum.

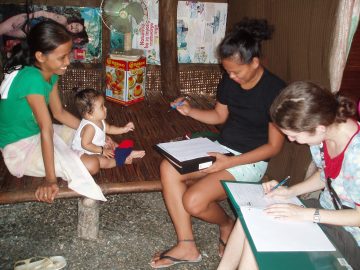

Interviews: community small scale fishing practices.

Photo: Danika Kleiber/Project Seahorse.

The second paper, Gender and marine protected areas: a case study of Danajon Bank, Philippines, was spearheaded by lead author and IOF PhD alumna Dr. Danika Kleiber, as well as Dr. Amanda Vincent, IOF Professor and founding Director of Project Seahorse, and Dr. Leila Harris of IRES UBC. The paper investigated gendered attitudes and participation in community-based management of no-take marine protected areas (MPAs) in Danajon Bank, the Philippines. Although the Philippines ranks highly on gender equality, strict gender roles are still evident in contexts like fisheries, making gender an important area of study.

No-take MPAs can present both advantages and drawbacks. Species recovery in MPAs can lead to increased biomass and a spill-over of fish from protected areas into fishing grounds, benefiting fishers. Conversely, their placement can also supplant fishers from fishing grounds.

“We found that women tend to glean – a method used to gather marine life in shallow waters or on exposed land – in the intertidal zone for shells and urchins, while men are more likely to fish from boats for fish or crabs. We wanted to know if MPAs had a different effect on women and men’s fisheries,” Dr. Kleiber explained. In addition to fishing itself, gender is also important in governance, because men and women’s participation in governance meetings can explain differences in management priorities and how fisheries resources are used.

Photo: Danika Kleiber/Project Seahorse.

Through interviews with fishers, the researchers found that men were more likely than women to state that their community MPA improved their fishing, but men and women were equally supportive of having one. Seventy-one per cent of respondents – both genders equally – said they would recommend an MPA to other communities, with fish protection and spill-over cited as the most common reasons.

Few men or women mentioned being displaced by an MPA. However, in several communities, interviews with local officials made it clear that the “no-take” rules for gleaning had been changed. In some cases, gleaning was allowed at certain times of the year, and in other cases the MPA boundary had been moved to exclude the gleaning area. This reflected the subsistence and social value given to the gleaning fisheries.

Photo: Danika Kleiber/Project Seahorse.

“Gleaning was often described as a what I started to think of as a ‘back-up’ fishery. People would say they gleaned when the weather was bad and they could not go fishing in a boat, or when they didn’t have money to buy food,” Dr. Kleiber said. “One leader explained that they moved the MPA out of the gleaning area because this is where people went to get food.”

Although equal numbers of men and women attended management meetings, women were less likely to actively participate in the management of MPAs. This suggested that the protected areas seemed to be managed and prioritized around men’s fisheries, and since women’s fisheries and management needs were secondary, their participation was also secondary. The researchers argued that gender and gender roles should be considered from the beginning of MPA development to include and represent a wider range of needs and interests within the community.

The papers Indigenous women respond to fisheries conflict and catalyze change in governance on Canada’s Pacific Coast and Gender and marine protected areas: a case study of Danajon Bank, Philippines were both published in the journal Maritime Studies.

By: Kristine Ho

Tags: Aboriginal fisheries, Amanda Vincent, Danika Kleiber, faculty, fisheries management, gender, Indigenous fisheries, IOF alumni, IOF students, Project Seahorse, Research, women