Recent research by IOF and Vancouver Aquarium researchers has found that apex marine predators – polar bears and killer whales – are affected by human pollutants. These contaminants are exacerbated by climate change factors, including the combustion of CO2 from fossil fuels, and pollution from chemical pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and mercury.

“This has serious implications,” said lead author, Dr. Juan Jose Alava, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries. “There is evidence that climate change may lead to contaminant burdens in fish and marine mammals, with a concomitant decrease in fish quality and nutritional value.”

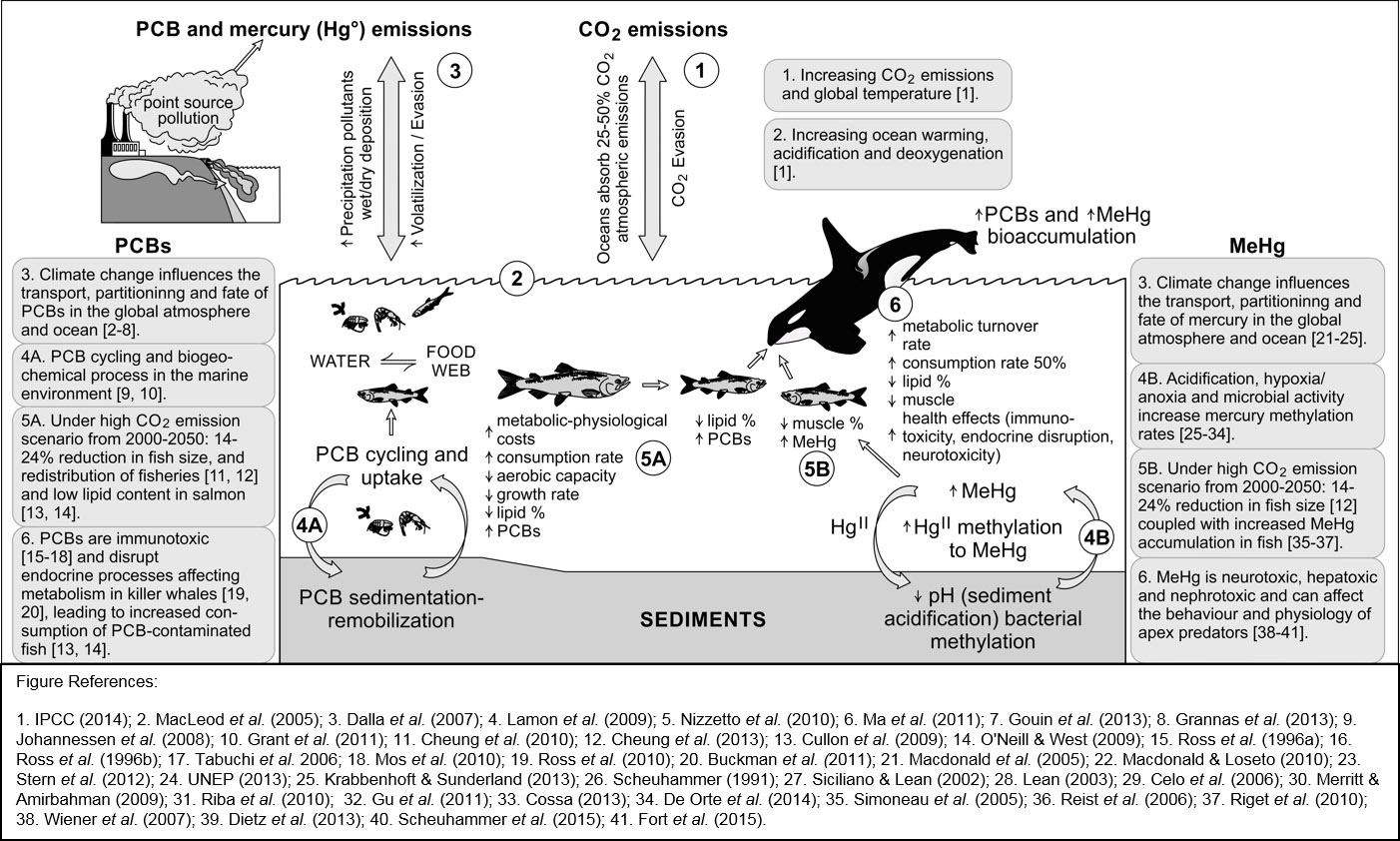

Researchers reviewed previously published studies and found that climate change is interacting with contaminants in the marine food web, particularly dangerous pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and organic mercury.

Researchers reviewed previously published studies and found that climate change is interacting with contaminants in the marine food web, particularly dangerous pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and organic mercury.

While species in industrialized areas may be most at risk, Alava noted the particular vulnerability of the Arctic climate. Based on published papers, “apex predators, such as polar bears, were more contaminated, mainly because they have shifted to other food sources – more contaminated sub-Arctic seals and seabirds as the sea ice is melting and shrinking. Arctic mammal species and wildlife populations already face environmental stressors from climate change, and now biological effects from pollutant exposure will exacerbate their risks.”

Alava also pointed to the endangered Southern Resident killer whale population, found in the Strait of Georgia and Puget Sound of the Pacific Northwest. “These marine mammals continue to be among the most PCB-contaminated organisms of the world, which raises serious concerns about their long-term survival. Increased pollutants in the Southern Resident killer whales ecosystem is likely from the consumption of fewer or smaller PCB-contaminated salmon (Chinook salmon), which are the whales’ main source of food and also affected by ocean warming. They have to hunt more for salmon that has declining lipid reserves or food value, and contain more contaminants. This affects their metabolism, makes them more susceptible to disease, and results in population declines.” Other human-made stressor conspiring against the survival of this killer whale population are underwater noise and physical disturbances, which will be further exacerbated by increased ship transportation and tanker traffic, as fossils fuel developments (pipelines) are taking place in our region.

And what of the biggest apex predator, humans? Alava predicts there will be many public health issues in the future. “These climate change stressors will affect socioeconomic aspects related to food systems including food safety. It also has important implications for human populations in some vulnerable regions, such as the Arctic where exposure to potentially harmful contaminants such as mercury through traditional seafood and a diet rich in marine mammals, is particularly high. This is a topic of significant concern research has also shown that indigenous populations, around the globe, consume 15 times more fish than non-Indigenous peoples.”1

Dr. Juan Jose Alava

For Alava and his team the next step is to undertake modelling, using the Ecopath with Ecosim (EwE) approach, to look at the long-term implications of pollutant strains. “We already see that PCB levels in killer whales is declining somewhat, due to the ban in the 1970s, however some cycling (PCB will settle on the ocean floor and stay there until the sediment is disturbed, which puts it back in circulation) occurs. For mercury, there are no regulations other than the Minamata Convention on Mercury to control this pollutant, and the major bulk is created by anthropogenic factors such as burning fossil fuels and gold mining, in addition to natural sources. What are the implications for the future? That is what we need to model.”

“Climate change is reshaping the way in which contaminants move through the global environment, in large part by changing the chemistry of the oceans and affecting the physiology, health, and feeding ecology of marine biota. These interactions can be either climate change dominant (i.e., climate change leads to an increase in contaminant exposure) or contaminant dominant (i.e., contamination leads to an increase in climate change susceptibility), and we need to understand their impact,” said Alava.

The study was published in Global Change Biology.

Funding provided for this study by: Mitacs-SSHRC joint initiative (Canadian Federal agency), OceanCanada Partnership (OCP) and the Ocean Pollution Research Program (OPRP) at The Vancouver Aquarium’s Coastal Ocean Research Institute.

1 For indigenous communities, fish mean much more than food, The Conversation, January 29, 2017.

Tags: Arctic, climate change, contaminants, faculty, IOF postdoctoral fellows, Juan Jose Alava, killer whales, marine mammals, polar bears, pollution, whales