WORLD JELLYFISH DAY

Coast guard ©Jessica Schaub

As climate change kills off competition, jellyfish numbers may rise, and one UBC researcher is working on increasing what we know about these creatures and their future.

“Growing up on the prairies, I was always drawn to the ocean. In my last few months of high school, I watched a documentary on the jellyfish crisis that was happening, and it got me thinking about jellyfish in a way I have never done before,” said Jessica Schaub, a Ph.D. student at the University of British Columbia who is embarking on an international research trip on jellyfish, courtesy of a grant from the Hugh Morris Fellowship.

Over 600 million years old, jellyfish are key components of ocean ecosystems, and are often not given the exposure and recognition they deserve. With a background in biology and oceanography, Schaub’s previous research focused primarily focused on jellyfish within food webs. Her paper on scyphozoan jellyfish focused on the composition of stable isotopes and fatty acids in jellyfish, and how these compositions changed based on what the jellyfish ate.

“One of the most common misconceptions of jellyfish is that because they are 95 per cent water, nothing eats them, and that they are not relevant to the food web,” said Schaub. “But that is not correct. They are very often consumed by other animals, but then the question becomes ‘why exactly are they being eaten, given that they are mostly water?’”

The answer may lie in the fact that jellyfish are usually found in abundance, often travel in groups or blooms, and are easy to digest.

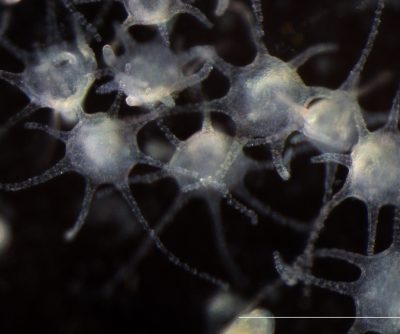

Moon jellyfish polyps ©Jessica Schaub

Schaub’s current focus is on “just jellyfishes.” She hopes to understand where other researchers are at in their work, and the big questions they are tackling. “You can have a good feeling for the literature, but it always makes a different to speak to researchers and see what they are working on now,” Schaub said. Having already visited Japan, Schaub’s next country is France, where she will learn how to collect and map out polyps in the Bages Sigean Lagoon, and identify them by their DNA.

Some human processes can actually be traced back to ancestors related to the jellyfish. With some jellyfish only a few millimetres in length, and others with tentacles as long as a blue whale, they are diverse species with a streamlined and efficient body structure that includes no brain, a mouth that doubles as an anus, and very primitive eyes that usually only sense light.

So, how do these creatures impact the ecosystems that they live in, besides eating and being eaten?

“Jellyfish also have other effects on ecosystems besides feeding interactions. For example, jellyfish release nutrients into the water when they expel waste and mucus. Just like human bacteria keeps us healthy, bacteria in the ocean can also help keep the environment healthy,” said Schaub. “The microbial community can be altered because of jellyfish, and this has consequences for the overall ecosystem.”

Jellyfish can also be very beneficial when it comes to climate change.

Moon jellies quadra ©Jessica

Schaub

Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is a major driver of climate change, and the ocean acts as a big carbon sink that transports carbon from the atmosphere and buries it deep within the sediment or in deep water. This gets sequestered for a long time, and helps to regulate the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

“One of the ways the ocean does this is through biological pumps,” Schaub said. “Plants and phytoplankton take carbon that originated in the atmosphere and fix it into sugars that are consumed by other animals. Because the ocean food web is often structured as big eats small, when animals eat and grow, they accumulate carbon throughout their life cycle.”

“Although jellyfish are mostly water, they accumulate carbon too,” explained Schaub. “Jellyfish usually only live for about a year, and they grow quite fast during this time. So, every year, you have huge amounts of jellyfish being born in the spring, and when they die, sinking quickly and taking their carbon away from the surface and into the deep ocean to be sequestered.”

These effects may have implications for ecosystems under pressure due to climate change. Jellyfish can survive at a range of salinities, oxygen levels, and temperatures that many of their competitors cannot. “Normally, you’re looking at animals because they are moving or dying, and their populations are decreasing. When it comes to the jellyfish, it actually seems that their competitors are dying out” Schaub said. “As we move forward, jellyfish may encounter less and less competition, and we have yet to figure out what that means for the future.”

Related Papers

- Using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to measure jellyfish aggregations is published in Marine Ecology Progress Series.

- An experimental and in situ application of stable isotopes and fatty acids to investigate the trophic ecology of moon jellyfish, Jessica’s MSc thesis, is published by the University of British Columbia.

Other stories about Jessica’s work

- This scientist is taking an international jellyfish tour to explore mucus and medusae, June 22, 2022

- Jellyfish researcher Jessica Schaub to take “international tour” thanks to Hugh Morris Fellowship, March 23, 2022

- Shedding light on mysterious jellyfish diets, October 14, 2021

- UBC researchers use drones to track jellyfish blooms, Feb 5, 2018

Tags: climate change, IOF students, jellyfish, Pelagic Ecosystems Lab, Research