Streams, rivers and lakes throughout B.C. are becoming less hospitable for fish. Shifts in precipitation and glacier and snowpack melt create years in which rivers rage or dry up unpredictably, disturbing the balance of underwater habitats. Humans use freshwater for crops and to generate hydroelectric power, competing with aquatic life for the resource. Hot weather, agricultural runoff, deforestation, and human waste combine to create a breeding ground for slimy, pea-soup coloured algae blooms that suck oxygen from water and suffocate fish.

A Dissolved Oxygen (DO) Logger ©Jordan Rosenfeld

The Applied Freshwater Ecology Research Unit’s (AFERU) job is to find ways to conserve freshwater species, test the effectiveness of current conservation strategies, and understand how freshwater fish are responding to changes in their habitats.

“We do research on conservation and management priority issues for freshwater fishes in B.C.,” said Jordan Rosenfeld, honourary IOF faculty member and a principal investigator in AFERU. “That includes habitat issues, but also things like assessing the habitat requirements of species at risk. Some of the work I do is on endangered and listed species in the Fraser Valley, like Salish sucker and Nooksack dace. Some of that work relates to evaluating the effectiveness of things like habitat restoration.”

One of Rosenfeld’s biggest projects right now involves “in-stream flows.” He is trying to understand how much water can be taken from streams before fish can’t live in them anymore — or how to find the right balance between human use and fish survival.

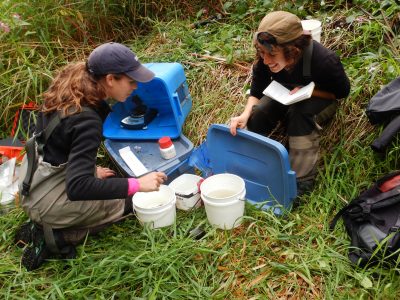

Deploying a DO logger ©Jordan Rosenfeld

Rosenfeld spends a lot of time working in small Fraser Valley streams, using nets to gather the drifting bugs that are a staple of fish diets, collecting samples of fish, or adding treatments of cobblestone and gravel to riverbeds as part of an experiment in fish habitats.

It’s all part of getting a clearer picture of how these water systems, so essential to the life cycle of species like salmon and trout, are changing in an era of increasing human-caused environmental impacts.

Heating up rainbow trout

Sarah Hnytka, a master’s student in the AFERU, has also been spending a lot of time in the water—the shallow water of the Athabasca River in Alberta. She’s studying Athabasca rainbow trout, a small rainbow trout listed as a species at risk, possibly due to climate change.

Hnytka wants to pinpoint the reason that Athabasca rainbow trout numbers are so low.

“A lot is known about rainbow trout, but the Athabasca ecotype is less studied,” Hnytka said. “Every 10 years you’re mandated to look at species at risk. We realized there’s pretty much nothing known about their thermal tolerance, in other words, how much heat these fish can take. Climate change is likely a huge driver for why these populations are declining, so it is a good time to take a look at this.”

Over the last summer, Hnytka was busy collecting Athabasca rainbow trout and pushing them to their limits in a test called a critical thermal maximum (or CT max) test. She and a team placed the fish inside a tank of water that warmed up by 0.3 degrees Celsius every minute. As the water warmed, the fish began to swim in agitated bursts. Once the fish appeared unresponsive or were unable to stabilize themselves, they were placed in a tank of cooler water, and then released unharmed.

Measuring fish ©Jordan Rosenfeld

“When this research gets incorporated into the next report on Athabasca rainbow trout, that’s when the policies can actually come in,” she said. “If we find that extreme temperatures are a critical factor in the decline of these rainbow trout, and they need more places to take refuge, it’d be awesome if we could come to policymakers to say, ‘Hey, these are the habitat areas we need to protect.’”

River and Lake Restoration for Sturgeon and Salmon

White Sturgeon, By Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife, CC BY-SA 2.0

“In some areas of B.C. there have been no juvenile white sturgeon entering the population since the 1970s,” McAdam said. “It’s catastrophic. I’m focused on figuring out what happened decades ago in these rivers and finding ways to reverse it.”

The decline of white sturgeon coincided with the construction of several hydroelectric dams in B.C. rivers. According to McAdam, when dams disrupt river flows, sand begins to fill in the crevices between rocks on the riverbed, the same crevices where white sturgeon eggs incubate and where young larvae need to hide. The increased mortality resulting from the loss of hiding spaces in early rearing habitats appears to be the underlying cause of recruitment failure.

Along with his students, Jennifer Fisher and Mikayla O’Ferrall, and industrial partners including BC Hydro, McAdam has been investigating white sturgeon spawning locations in the Nechako and Columbia rivers, learning which types of habitats the sturgeon prefer to use for spawning, and then exploring how to restore those habitats by reducing sand buildup and adding new substrates such as gravel and cobblestone.

However, it’s not as simple as removing sand from the bottom of the river or adding new, clean substrate.

©John Gray

Shannon Harris, a limnology specialist at the AFERU, understands the patience and determination it takes to restore fish populations that have been disturbed by dams and human activities. She’s working on four separate restoration projects in Adams Lake, Alouette Lake, Wahleach Lake, and Kootenay Lake, all of which are either reservoirs or lakes affected by dams.

Harris and her team of Heather Vainionpaa and Jennifer Sarchuk, do experimental work adding agricultural grade nutrients to these lakes to restore ecosystem productivity and reestablish healthy, sustainable fish populations.

One project that has Harris particularly excited is her Alouette Lake work, which is restoring nutrients to support ecosystem productivity and the growth of the lake’s rare ecotype of sockeye salmon.

When the Alouette dam was constructed in 1928, habitat connectivity was impacted resulting in a land-locked population of kokanee salmon. Alouette’s salmon are unique, spawning deep underwater, unlike the more common stream spawners most are familiar with.

Since 1999, the Province of B.C. has used nutrient restoration to recover ecosystem productivity and has fueled the growth of a robust food web to support a 10-fold increase in kokanee salmon populations. These healthy kokanee populations support an in-lake kokanee fishery and are helping to support bulltrout recovery.

They are also helping to restore the life history of Alouette salmon by making them anadromous (having both a freshwater and a marine life stage) once again. In cooperation with BC Hydro, an annual spill has allowed the kokanee smolts to migrate back to the marine environment. With the help of BC Correction’ trap and truck program, they have returned annually to the reservoir since 2007.

“Without our program, the restoration of sockeye salmon in the watershed would not be possible,” Harris said.

“Our work on Alouette is exciting because it checks off a lot of boxes. You’re maintaining biodiversity of salmon stocks, maintaining a rare ecotype stock, restoring in-lake ecosystem productivity, and checking off re-establishing the anadromous fishery which is also really important for our Indigenous partners. These are really valuable outcomes for the Province of BC.”

Islands in the stream

John Gray collecting dace ©Jordan Rosenfeld

Measuring dace ©John Gray

“Because of agriculture, even as far back as the early 1900s, a lot of these creeks lost their meandering tendencies where you have diversities of flow that result in the accumulation of certain substrates, like cobble and gravel,” Gray said. “You also lose a lot of the original substrate in a system, which provides refuge from predators and flow, and provides a great source of prey.”

Nooksack dace like “riffles,” the rocky high points of streams and rivers where water flows the fastest and mixes with oxygen. Gray’s research involves restoring these riffles to areas that have lost them over time.

Building a riffle ©Jordan Rosenfeld

Data from the project is coming back now, and soon Gray will be able to see whether the dace take to the riffles.

“If I get nothing else, I hope I am able to help with conservation of endangered species,” he said.

It’s a sentiment shared by Jordan Rosenfeld, who thinks the most important part of the work he does is helping to protect fish.

“I think the greatest success of this lab has been making people understand the importance of small streams and small stream habitats,” Rosenfeld said. “The importance of protecting those habitats, and also better defining what constitutes critical habitat for endangered species so that they can be protected under existing legislation, and providing that information to fisheries management agencies so they can use it to improve habitat protection.”

Tags: Applied Freshwater Ecology Research Unit, British Columbia, fish, fish stocks, fisheries management, freshwater, Jordan Rosenfeld, recreational fisheries