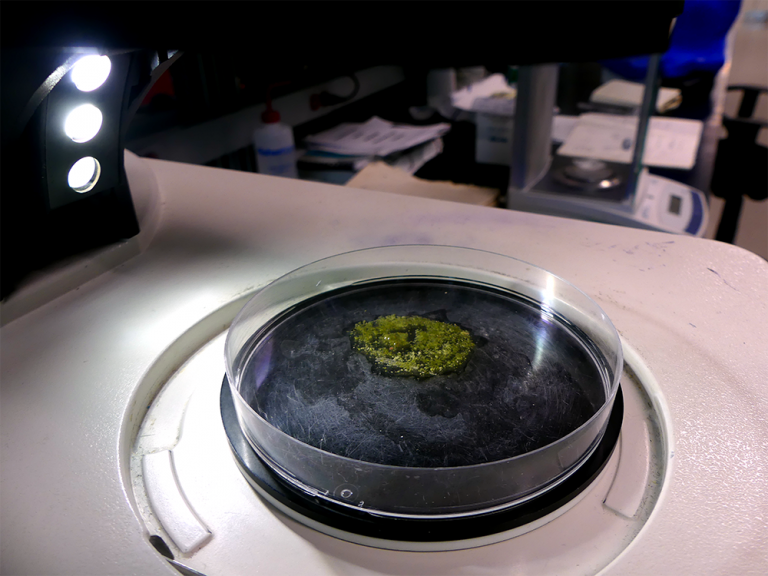

Vanessa Fladmark working at a microscope.

Meet student Vanessa Fladmark, a Masters student, oceans outreach enthusiast and professional salmon stomach detective. She is mainly at the Marine Zooplankton and Micronekton Laboratory of the Department of Earth and Ocean Sciences but is also connected to the Pelagic Ecosystems Lab and UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF).

Coming to UBC from Haida Gwaii, Vanessa studies juvenile pink and chum salmon and what they eat in BC’s coastal waters – by looking at their stomach contents.

Tell us about yourself.

My name is Vanessa Fladmark, and I’m from the Haida Nation on Haida Gwaii. I’m currently a second year Masters student working with Evgeny Pakhomov and Brian Hunt, pursuing a degree in biological oceanography.

Vanessa Fladmark.

What are you researching?

I study juvenile pink and chum feeding ecology in coastal British Columbia, focusing in the area around the Discovery Islands and the Johnstone Strait. This involves looking at their feeding during the first couple months at sea, after they migrate through the Strait of Georgia. I look at this specifically with a bottom-up focus; investigating their stomach contents to determine what the salmon were eating and what zooplankton would have been available in the water.

My main research questions involve comparing areas of different productivity, and how pink and chum salmon are interacting and feeding under different conditions. For example, what are these species foraging for when the abundance of zooplankton in the ecosystem changes? Do they compete with each other or do they occupy different niches, which limits competition between species? How are they behaving when different zooplankton communities exist in the water? Those are some of the things I’m looking at.

What tools or techniques do you use to study salmon stomachs?

I use a microscope to look at the stomach contents of juvenile salmon and identify, count, measure, and weigh all the different things they’ve consumed, from zooplankton to microplastics to other fish. I get to see not only what they are eating, but how much they consume.

While I can assess this visually, there is also a calculation that helps me determine how much salmon are consuming compared to their body weight. I’m still analyzing the data now, but so far in some areas we’re seeing that some salmon are eating a lot, more than 100% of their stomach’s fullness, while in other areas their stomachs are pretty empty. It’s interesting because what and how salmon eat can be really, really diverse across the ecosystem.

Where do you get these salmon samples from?

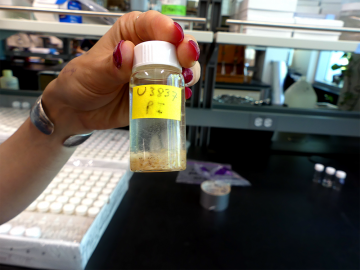

Echinoderm larvae from a salmon stomach.

We are partnered with the Hakai Research Institute up on Quadra Island, which has a Juvenile Salmon program where they collect salmon every year. Typically, during the salmon’s main outmigration period in May through to July, they collect and dissect sockeye, pink, chum, and a little bit of chinook, Coho, and herring. Fish are assessed for parasites and samples like scales, otoliths, muscle tissues, and stomachs are collected. After this, I get access to samples for the years I’m evaluating – 2015 and 2016.

Hakai also takes zooplankton tows, which provides me with information to evaluate which organisms are in the water, compared to what the salmon are actually eating. I can see if the salmon are picking out certain organisms in the water to consume, or are avoiding other organisms.

Why did you choose this research area in particular?

I did a Directed Studies course in my undergrad with Evgeny Pakhomov, looking at fish diets but in surf smelt, herring and anchovies. I thought it was really cool, weird, and niche work to be cutting open fish stomachs. It’s fun to look at something and identify what type of zooplankton it is – kind of like being a detective.

Sometimes I see something and I’m like, “What is that? It’s got half of its body but I think I can still identify it…” It fits this puzzle and tells you what this fish experienced, and I find that really interesting.

Why study salmon, especially pink and chum?

I worked for a year in the lab under a Pacific Salmon Foundation grant and did work with all sorts of different species of fish. Salmon, I think, are particularly interesting. I picked pink and chum because they’re co-migrators of sockeye, which is the species people are usually really concerned about because sockeye are in decline. But nobody’s really looking at pink and chum, which are possible competitors, and it’s crucial to look at potential interactions between salmon species.

Salmon are so important: economically, socially, culturally, ecologically – in freshwater, ocean, and terrestrial systems. They’re at the centre of everything in B.C. And, being from Haida Gwaii, my people love salmon, and I want to be able to graduate and bring this knowledge back to my community.

What do the Marine Zooplankton and Micronekton Lab and Pelagic Ecosystem Lab investigate?

It’s hard to describe because our research is so diverse, but generally we’re looking at multiple levels and organisms rather than a single thing. There are people looking at jellyfish, biogeochemistry, using DNA genetic testing, and all sorts of things. A big focus is on food chains and the interaction of food webs – what’s eating what, and how that is influenced by bottom-up and top-down controls like the properties of the water and higher trophic predators, respectively.

What’s really cool about the salmon work we’re doing is that, overall, we’re looking at each life phase of salmon. Thomas Smith is looking at the freshwater phase, Samantha James and I are looking at the early marine stage, and Caroline Graham is doing a literature review on salmon diets in the open ocean. Boris Espinasse is looking at stable isotopes in salmon, which gives you a one-month long idea of what they’re eating by looking at their tissue, while stomachs give you a recent snapshot. There are a lot of different things that we’re looking at, and each person is kind of like a different piece of the puzzle.

My work really ties in with Samantha, who is also investigating salmon stomach contents in the years 2015 and 2016, but in sockeye. Eventually the idea is to compare our research and see how different salmon are feeding differently.

Stored stomach contents of a pink salmon, full of krill.

What are your favourite and least favourite things about your research here?

I really do enjoy fieldwork, even though I’ve been more lab-focused. But I’d also say a big part of it is the community that we have in the labs and at UBC. In both my labs, I get to collaborate with these brilliant people, talk about zooplankton and salmon with them, go to conferences together and so much more. It’s really great to have a bunch of brilliant friends so I’ll miss that when I graduate.

My least favourite is just living in the city, because I’m from a very, very small town. So that’s definitely the most challenging thing, being away from the community. In the city, there’s so many people and that can be overwhelming. It’s a tough juggling act: I get to learn cool things, but I’m not living where I want to be.

What do you like to do when you’re not doing research?

I actually do a lot of volunteering for ocean-related things, so even when I’m not in the lab doing my ocean research I’m out there talking to the public. I’ve talked with high school students and I’m really involved in shoreline cleanups like the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup; I’ve done like ten of those and that’s really become the thing I do for fun, going to the beach and picking up garbage with other people. As part of the Ocean Leaders course I took, we actually analyzed the data on cleanups in B.C., which was really cool.

Why do you do oceans outreach?

It’s one thing to study the ocean and to work in isolation in academia, and it’s another thing to reach out to people and be like, “This is what I’m working on and this is why it’s important, and here’s how you can help.” Outreach keeps me inspired to keep going through grad school when it gets really tough. Seeing other people getting excited about oceans research and talking about it reminds me why I’m doing what I’m doing, when I’ve been lost in the microscope for too long.

I also want to inspire more people to go into science, especially Indigenous students, because I’ve found it very challenging to move away from my community so I know how much of a struggle it is. It’s also difficult to put so much time into school when you could be in the community, making a difference on the ground. But I do believe education and creating networks are really worthwhile, because I want my community to be empowered to do even more Haida-led research and sustainable marine stewardship.

Tags: IOF students, plankton, Research, salmon, Shoreline cleanup