With increasingly more pressure from resource development and climate change, protecting the Arctic and its wildlife is more important than ever. But which parts of the Arctic should be prioritised for protection?

A diverse group of international researchers collaborated to try and answer this. They mapped out key locations in the Arctic where top predators converged, called “hotspots.” Since these hotspots are areas with high levels of biodiversity where various species come together, they are crucial for conservation; protecting them means protecting multiple species. The study mostly took place in Canadian Arctic marine waters, but also in parts of the United States, Greenland, and Russia.

Dr. Marie Auger-Méthé

“This study was unique in that so many researchers came together and shared their data, and this allowed us to have a broad view of how animals move in the Arctic,” said Dr. Marie Auger-Méthé, Assistant Professor at UBC’s Institute of Oceans and Fisheries and the UBC Department of Statistics, who specializes in modelling animal behaviour using movement data. She is one of the study’s authors, along with her student Ron Togunov, a UBC Zoology PhD candidate at the Institute of Oceans and Fisheries. Togunov, who studies the foraging patterns of Arctic marine mammals, is also part of the Marine Mammal Research Unit (MMRU).

The study was the first of its kind to map areas where multiple Arctic predators converge, allowing the researchers to look at protecting habitats for multiple species, unlike past studies that concentrated on single-species conservation.

“Without such collaboration, it would be impossible to identify areas that are important for such a broad range of species and across such a wide area of the world,” added Auger-Méthé.

Ron Togunov. Credit: UBC Marine Mammal Research Unit

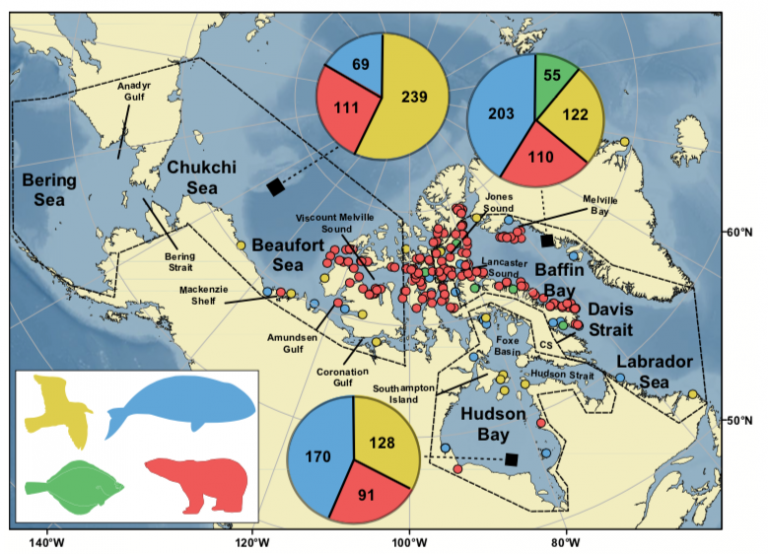

To find these hotspots, the researchers looked at existing animal tracking data across four highly mobile species groups, which were cetaceans and pinnipeds, polar bears, seabirds, and fishes. The data informed the researchers about where these predators were located at different times of the year and where they converged, giving insight into which areas should be protected.

In summer and autumn, the researchers found most species were usually located within the continental shelf, while during winter and spring, hotspots occurred in areas of moving pack ice.

When comparing currently protected areas and hotspot locations, the researchers found that there was little overlap. Only 5 per cent of the summer-autumn species hotspots were protected, while 7 per cent of the winter-spring species hotspots were protected. This shows that areas that are crucial for Arctic marine predators are largely left unprotected.

This map shows the entire study area divided into 3 regions: West, East and South. The coloured dots show where species were captured and tagged, while the numbers in the pie chart show how many individual animals were tagged in each species group. The species groups are shown in the bottom left (yellow for birds, green for fishes, blue for cetaceans and pinnipeds, and red for polar bears).

Given the various threats endangering the Arctic, it is important that policy-makers are prioritising protection for the most important conservation areas. In the Canadian Arctic, protected areas are usually small and designed to protect single species. Since most of the hotspots identified by the study were found in Canada, and since Canada has committed to protecting 10 per cent of its marine waters by 2020, this research highlights many potential areas for future marine protection.

Since most of the hotspots identified by the study were found in Canada, and since Canada has committed to protecting 10 per cent of its marine waters by 2020, this research highlights many potential areas for future marine protection.

The researchers also call for more research collaboration about areas where multiple species could be protected. The Arctic, and its species, span across multiple nations, and so sharing international data and engaging in international conservation efforts are important.

“The Arctic is changing at a remarkable rate. As sea ice is declining, the habitat of animals is changing drastically, shipping is increasing, and the potential for new fisheries are expanding,” explained Auger-Méthé. “Because the Arctic is still relatively undeveloped, it is crucial to understand what areas are important to conserve before potentially irreversible changes are made. Conservation should be done in conjunction with the communities that rely on these animals, and it should be done now.”

The article “Abundance and species diversity hotspots of tracked marine predators across the North American Arctic” was published in the journal Diversity and Distributions.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institute of Ecology and Evolution (CIEE), which is now hosted at UBC in the Biodiversity Research Centre.

Tags: Animal movement, Arctic, Conservation, Faculty, IOF students, Marie Auger-Methe, Marine Mammal Research Unit, Research, satellite data, SERG, tagging