Private companies may secure short-term profit, but deep sea mining comes at a major cost for humanity.

Deep sea mining boat, image compiled by Lubna

Deep sea mining will produce far too few benefits for the harm it will cause. That is the result of an analysis by marine scientists and policy experts from around the globe, led by Dr. Rashid Sumaila from the University of British Columbia.

While advocates of deep-sea mining say that the investment is needed to provide the metals needed for electric car batteries and other electronic infrastructure for a carbon neutral economy, opponents point to the irreparable damage that it would have on the environment, including delicate habitats on the seafloor, and the detrimental effect it will have on developing nations, including those that may directly benefit from deep sea mining in their area.

The researchers looked at the cost and benefits for private mining companies and their investors, developing countries, including those who could directly benefit from deep sea mining in their area, countries engaged in terrestrial mining, and ‘nature’ itself, and found that while there would be some short-term private company profits, over the longer term the benefits would dwindle. Most particularly for developing nations, the natural world and humanity as a whole.

“On a purely economic level, capital and operational costs would be very high. Approximately US$ 4-6 billion. Projected revenues are estimated to US$ 9-11 billion, however that is over a thirty-year period,” said Dr. Rashid Sumaila, lead author and professor in UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF) and the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs. “Add to that the operational costs of refining the polymetallic nodules mined, at best the annual profit would be in the region of US$1.2 billion. Investors may like those numbers; however, they are also likely to have those profits chipped away at by both litigation and business model risks, as surges in climate change and biodiversity impacts take their toll, along with foreseeable litigation from aggrieved countries, communities and other stakeholders impacted by deep sea mining.”

Developing countries, including those who are attracted to deep sea mining for its potential to generate economic benefits such as tax revenues and jobs, will gain little, according to the commentary. “Sponsoring member states will likely benefit from a corporate tax payment of 25 per cent – approximately US$3 billion. However, it will be divided amongst the states over the same 30-year contract period,” said Dr. Lubna Alam, co-author and research scholar at the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries. “It will deliver pittance to those countries.”

Photo by Carlos Muñoz-Royo

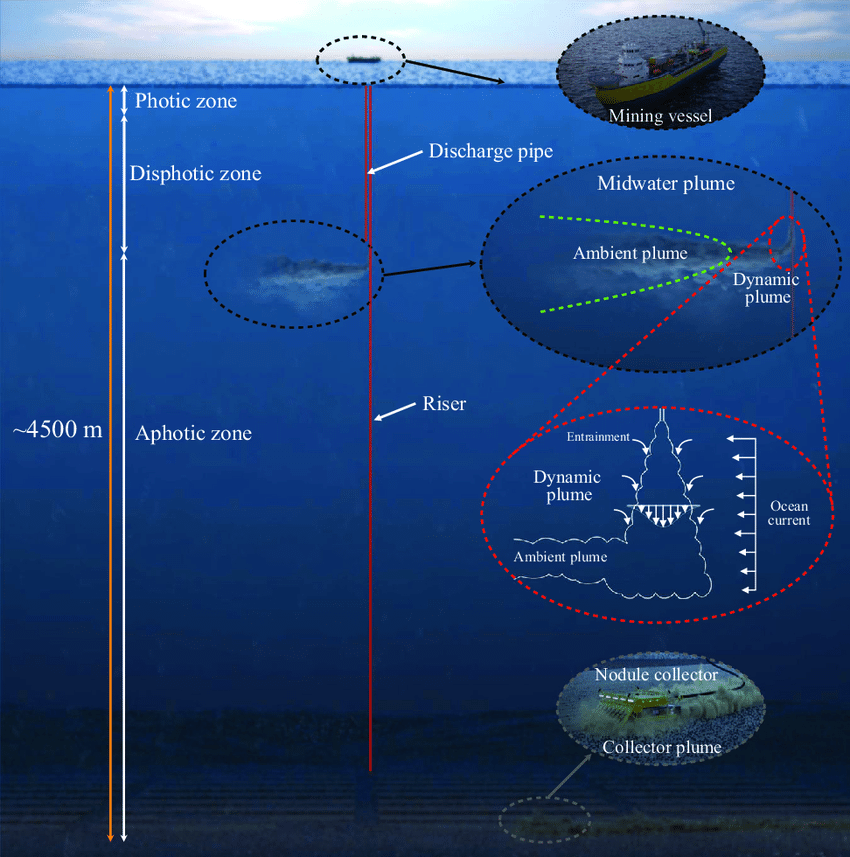

The ecological damage would be even worse. “We know so little about our oceans, and even less about the seafloor itself. The irreversible damage that it is going to do to very delicate ecosystems is horrific,” Sumaila said. For instance, a single mining operation could release up to 80 km³ of sediment plume into the ocean every day, spreading to an area of up to 24,000 km² in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone alone. This plume is capable of reducing light penetration and water oxygenation while at the same time dispersing toxins and radioactivity.

Dr. Sumaila does point to some international movement on this issue. The International Seabed Authority (ISA), an intergovernmental organization established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to regulate the exploration of minerals found on the international seafloor, began its most recent round of meeting on the subject on October 30th, and already 23 countries, including many small island developing states who would be directly affected by deep-sea mining, as well as large developed countries including Canada and the United Kingdom have asked for a moratorium, or ban on deep sea mining.

“At the time when safeguarding biodiversity and ecosystems is paramount, this analysis of deep-sea mining’s economics is timely,” said Dona Bertarelli, philanthropist and ocean advocate who funded this research. “Highlighting short-term gains for a few, but enduring costs for coastal communities and states most reliant on a thriving, healthy ocean. I hope this study will prompt International Seabed Authority member states to stop and reflect.”

“The minerals on the international seafloor are humanity’s common heritage,” said Dr. Rashid Sumaila, lead author and professor in UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries. “However, our analysis shows that while deep sea mining may provide short-term profits for mining companies and marginal benefits to developing countries, long term benefits will be minimal due to anticipated business model and litigation risks, public opposition, and competition from land-based mining. In fact, this action could come with dire, irreparable loss to nature and humanity as a whole.”

Twenty-three countries who have joined the ‘Global Tide of Opposition to Deep Sea Mining’

2022: Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Fiji, France, FSM, Germany, New Zealand, Panama, Paulau, Samoa, Spain

2023: Brazil, Canada, Dominican Republic, Finland, Ireland, Monaco, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Vanuatu

To engage in deep-sea mining or not to engage: what do full net cost analyses tell us? was published in Nature

Tags: contaminants, deep sea mining, faculty, International Seabed Authority Assembly (ISA), mineral deposits, mining, ocean ecology, pollution, Rashid Sumaila, sea floor, UNCLOS