While some oceans researchers spend their time studying charismatic marine mammals like seals, launching tracking devices at whales, or monitoring the migration patterns of vital human food species like salmon, Curtis Suttle, the professor and principal investigator of the Marine Virology and Microbiology Lab (or Suttle Lab), along with his long-time partner, Amy Chan, a research scientist in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, have, for the past 30 years, focused on aquatic life that can only be seen with an electron microscope: marine viruses and bacteria.

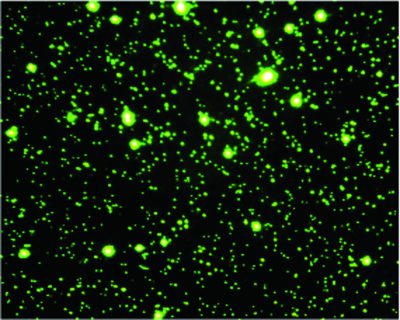

Viruses and bacteria in a drop of seawater from the Arctic Ocean stained with a fluorescent dye (image credit: Jerome Payet)

The smallest microbes are viruses, particles that infect and replicate themselves in a host organism’s cells. According to Suttle, “Our knowledge of marine viruses is very remedial, mainly because no one has looked.”

At the Suttle Lab, researchers’ primary goals are to identify previously unknown viruses to understand how those viruses affect marine life. This is a Pacific-ocean-sized task, as the vast majority — millions upon millions — of these infectious agents are unknown to us.

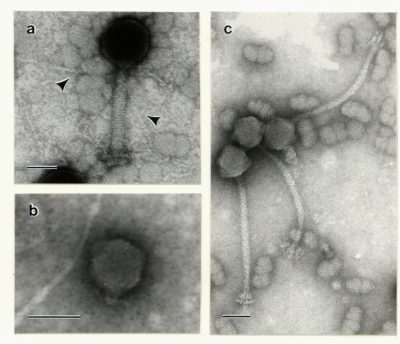

Three different types of viruses that infect phytoplankton (image credit Amy M Chan)

“When we recently did work looking for viruses in salmon, we found several new viruses that no one knew infected salmon, some of which no one knew infected fish,” Suttle said.

Amy Chan has been working alongside Suttle since before they were at Stony Brook University, New York, where they witnessed the discovery of abundant viruses in the sea.

That initial partnership led Chan to dedicate her professional life to uncovering viruses and bacteria that live in water.

“It’s exciting — when you find something that no one else has found before, when it’s the first ever,” Chan said. “Here at UBC, I isolated the first RNA virus that infects and kills a red tide, bloom-forming algae.”

Chan’s viral-discovery career has sent her on journeys thousands of feet deep into the earth down old mine shafts in Timmins, Ontario; into the burning hot [50-degree hot] “crystal caves” of Chihuahua, Mexico; and on countless research cruises throughout the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean.

She’s also seen the field grow into what it is today.

“It’s a pretty new field still,” Chan said. “It started in the early 90s. The first decade it was a small, intimate group, but now we have huge meetings.”

Identifying all of these viruses may seem daunting, but for Tianyi Chang, a PhD student in the Suttle lab, the opposite is true.

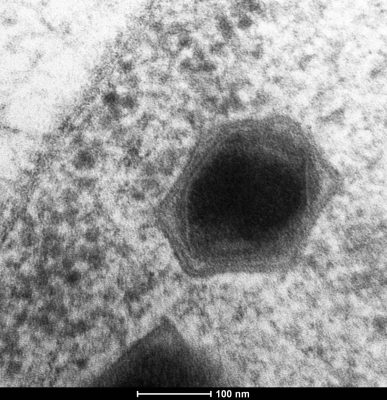

Giant virus inside a microzooplankton (image credit Matthias Fischer)

Chang went on a month-long expedition aboard a research ship travelling from Hawaii to Chile to collect samples of zooplankton for virus identification. He and his colleagues found dozens of viruses infecting copepods, a group of near-microscopic crustaceans. What’s more, the viruses they identified were mostly RNA viruses, viruses that use RNA and not DNA to encode their genetic information, and that tend to mutate faster than DNA viruses. It was the first study that Chang knows of to find RNA viruses in copepods.

Chang also recently found over 30 RNA viruses inside sea lice, parasitic copepods that latch onto salmon and can kill them when they suck up blood and mucous and leave lesions on salmon flesh. He thinks the viruses may be used to control sea lice populations and save salmon.

“We’re not able to identify the one magic answer”

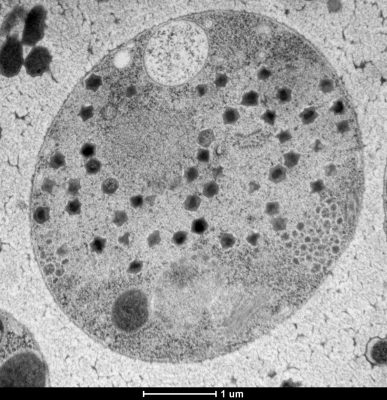

Microzooplankton infected by viruses (image credit Matthias Fischer)

“In the wild you don’t find many sick fish because sick fish don’t survive very long. If you’re a bit slower, a seal or an orca is going to come eat you,” Suttle said.

Although researchers can see viruses replicating inside fish, fish deaths could be a consequence of any number of things, including ocean pollution and ocean warming.

Pinpointing the exact cause of mortality in sea organisms is a challenge that Jan Finke, a post-doctoral researcher with the Suttle Lab and Hakai Institute, understands well. For the past three years, he has tried to uncover what’s been killing oysters in B.C.’s oyster farms.

“Pathogens are natural but in oyster farms, where you have a really high density of oysters, that disease and mortality turn out to be bigger problems. Entire stocks will just die off within short timespans, sometimes days and then everything’s just gone,” Finke said.

Finke hoped that he would be able to identify one or a few viruses and bacteria that were clearly responsible for wiping out racks of oysters. However, the problem turned out to be much more multi-faceted than Finke expected, and he’s still reckoning with the mystery.

“We got ideas but we’re not able to identify the one magic answer to everything yet,” he said.

Unlike oyster farms in Australia and France, where researchers found specific pathogens that were linked to large oyster mortality events, B.C.’s oyster problem seems to involve a “cascade” of many different viruses and bacteria, as well as environmental stressors such as ocean acidification and warmer ocean temperatures.

“Even in human diseases it’s more and more of this concept of, well, you’ve got a primary pathogen and then you’ve got a secondary infection on top of that, and that second infection is what really complicates things,” Finke said.

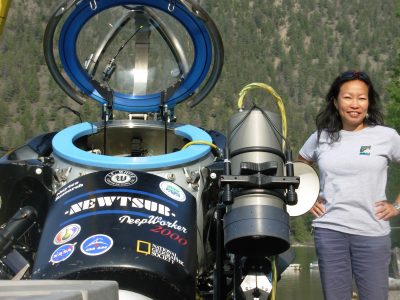

Amy Chan next to submarine exploring alkaline lake for NASA project

“We need them to survive”

Curtis Suttle thinks it’s important for people to know that viruses, despite their frightening reputation, have a role to play in Earth’s many ecosystems.

“We’ve lived with them for forever; our most ancient ancestors coevolved and coexisted with viruses,” he said.

When viruses kill organisms in the environment, they help recycle nutrients that sustain other life. Thus, they perform the essential task of resupplying nutrients to the various ecosystems they are a part of.

“The thing that I always try to get across with everything we do, is that viruses are part of the natural world,” Suttle said.” If there were no viruses, we would not be alive. We need them to survive.”

Tags: biodiversity, Curtis Suttle, faculty, Marine Virology and Microbiology Lab, plankton, Research, viruses