New modelling from the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF) indicates that microplastics (pieces of plastic less than five millimeters) accumulate in marine biota, but do not appear to magnify as they travel through marine food webs from zooplankton into fish, and ultimately marine mammals.

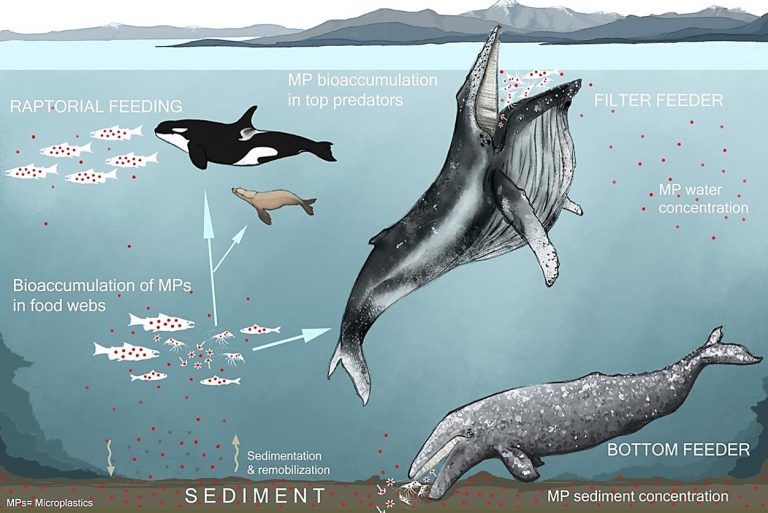

An illustration showing pathways for bioaccumulation of microplastics (MPs) in marine mammalian food webs, indicating the feeding preferences and foraging strategies in marine mammals (e.g., fish-eating killer whales, pinnipeds, filter-feeding humpback and bottom-feeding grey whales) and potential microplastic exposure via prey (zooplankton/krill, benthic crustaceans and fish). Artwork: Nastenka Alava Calle.

“They are a kind of new class of emerging contaminants that are bringing a lot of attention about the potential risks for marine fauna and coastal communities,” said Juan Jose Alava, principal investigator of the Ocean Pollution Research Unit (OPRU), and a research associate at the IOF who authored the study. “They are persistent because they take a long time to break down, and the material can cause some damage and health effects in marine organisms.”

That damage includes things like blocking the digestive tracts of fish and leaching toxic chemicals contained within the plastics into the tissues of marine life.

Alava built a computer model to test whether microplastics biomagnify (appear in larger and larger quantities or concentrations as they move up at each trophic level in the food web) and bioaccumulate (build up within the GI tract or other organs of marine life at a faster rate than they can be expelled). The model used sample data of water with low, medium and high concentrations of microplastics combined with data about the food webs, digestive processes and dietary habits of humpback and killer whales in the northeastern Pacific Ocean.

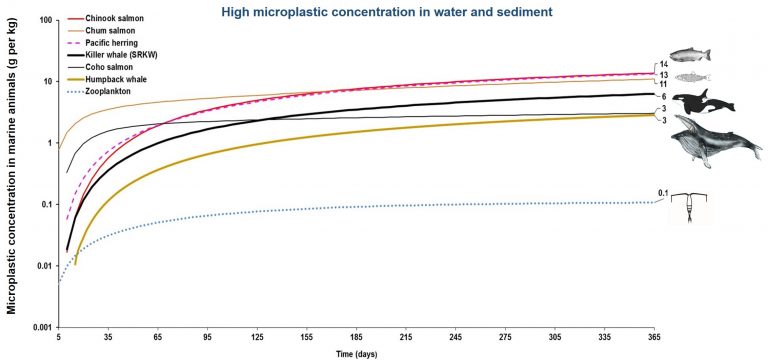

Figure showing the projections under a scenario of high microplastic concentration to predict the potential bioaccumulation in marine species of the food web. From the bottom to the top: zooplankton, humpback whale, southern resident killer whale, Pacific herring and Chinook salmon.

The models revealed that microplastics biomagnified scarcely in the two whale species examined. However, Alava cautioned that to get a more accurate picture of the dangers of microplastic biomagnification, the model needs to be applied to more food webs. Moreover, the models indicated that microplastics do bioaccumulate, especially in smaller species of zooplankton and fish, and thus pose a threat to marine life.

“The takeaway is that we learned that the water and sediments are polluted with microplastics. The global ocean is basically a dump,” Alava said. “We need to change our behaviours, our preferences and our consumption. The world’s population is depending on plastics. Yet, they’re everywhere. The idea is to change to a more clean, plastic-free and biodegradable source of products.”

Alava’s model is freely available and he hopes that other researchers will make use of it to see whether microplastic biomagnification presents risks to species not yet examined.

A visual snapshot on Microplastic bioaccumulation/biomagnification can be found at the following microplastic bioaccumulation video Microplastic Bioaccumulation Infographic from Nastenkita Alava on Vimeo.

Tags: IOF Research Associates, Juan Jose Alava, OPRU, plastic, pollution