©Marie Auger-Methe

The IOF interviewed two of our researchers, Ron Togunov and Katie Florko, who have each researched narwhals and have contributed to helping us learn more about these shy creatures.

Katie Florko

Two of your research papers have been about narwhals, Katie. What inspired them?

The two papers were actually from the same project, and the data was collected simultaneously. The main goals with those papers were to investigate an area that’s called the last ice area. In the Arctic, there’s been this kind of polar cap of multiyear sea ice. And because there’s this really heavy sea ice, there’s often not a lot of productivity. But what’s been found is that the sea ice has been shrinking. The size of it is smaller, and it’s kind of retracting northwards. And the idea is that this area, it’s at the tip of northern Canada at the tip of Ellesmere Island is expected to be the area where we’ll have the last sea ice in the summer.

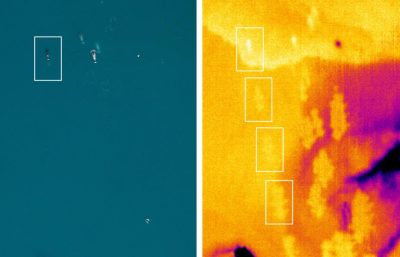

The narwhal (top left) has left a path of upwellings that can only be seen clearly in the infrared image at right. Credit: Katie Florko and Cody Carlyle

Sea ice is ice that forms on the surface of any marine waters. It covers the surface of the water, and commonly serves as a substrate for algae to grow in. That then feeds other levels of the food web. And it also serves as a physical platform for a bunch of marine mammals. Seals and walruses will use it to haul out and pop out of the water and use it as a platform to rest. And it’s also really important because it’s what polar bears use as well. They use it for traveling and for hunting and for finding mates.

So, how did you monitor the sea ice and what was going on in the water?

We went up in a small, fixed wing plane, and the belly of it was open. We put a couple of cameras in the bottom of the plane while we were flying, and these cameras are really helpful. We also had a visual camera that was taking photos every two seconds and that has a really high resolution.

We also brought an infrared camera that was mounted right beside the DSLR camera. And the idea with the infrared is that it could help us pick up animals that are really hard to see.

Kate Florko

The first thing that was really cool was how we detected in the narwhals. So, we’re flying around. And then suddenly on the infrared, we saw these really interesting patterns that were humongous. With these narwhals, what we were seeing is this huge trailing pattern behind them. And then we looked into it and found that that was what we call a fluke print — the mixing of water from the swimming up the animal.

And then the other really cool thing was the narwhals that we saw with the infrared were the most northern narwhal that have been observed. And it’s because the ice is retreating, and that these really northern areas are becoming warmer and they’re becoming accessible to animals.

How did it feel seeing the narwhals?

I would say it was bittersweet, I had mixed feelings. I mean, it was cool to see narwhals. And it was cool to see the northern most narwhal, but it was also concerning seeing them in an area that’s typically covered in ice. We also don’t know a whole lot because this area hasn’t been observed before so we don’t know, maybe they have been coming here for like the previously shorter summer seasons. Maybe they have been using this area. But regardless, it does seem like a bit of a canary in a coal mine.

Ron Togunov

Ron Togunov. Credit: UBC Marine Mammal Research Unit

The project I was part of it was primarily organized by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). For this particular project, they were working with a community out of Pond Inlet on Baffin Island. The narwhal for them is an important species for subsistence harvesting, and also culturally, but there were some iron mines that had opened in that area a few years ago. The community was concerned and interested about the effects that shipping might have on the narwhals using that area.

With iron mines on Baffin Island, what effects on the narwhals were the communities worried about?

Narwhals spend the wintertime in Baffin Bay, which is the big body of water between Nunavut and Greenland. And then, when the ice melts, they migrate north, and they go into the fjords around Baffin Island. And that also happens to be where the mine would be shipping the iron from, and they would only be able to ship during the narrow window of the year where there’s no ice. That also happens to be the narrow window that narwhals like to go there for.

How is the DFO tracking these narwhals?

They had pretty high-resolution GPS tags that they deployed. And they wanted to see what the narwhals did when the ships were coming through. And they were also interested in more broad skill patterns. Try to understand which fjords they’re using and try to identify why they might be using those areas.

Narwhals. © Marie Auger-Méthé

The original plan was to deploy about 20 tags per year. And they had had some really great success the year before I came onto the project. Usually there’s about 3000 narwhal that are moving in and out of this area [Tremblay Sound], which was where the field work was being done. A lot of narwhals come through, pretty close to the shore and the individuals get caught in the nets, they’re pulled to shore, the tag is put on, and then they’re released. And this all happens within a span of 20, 30, 45 minutes.

The year that I came, they went down from about 3000 whales to only about 300. I think they only managed to deploy five tags. They ended up drastically downscaling the operations and the primary observational research was on how many narwhals are coming in and out, estimating the number of juveniles and adults and males and females, and then using drones, to survey populations and monitor behavior, as well as deploying hydrophones, which are acoustic microphones to record number of individuals. You can figure out different behaviours based on the types of sounds that they’re making. There are pretty clear signatures of when they’re searching for food and when they’re actively hunting for food, when they’re just socializing.

Tags: Arctic, IOF students, Marie Auger-Methe, narwhals, SERG, whales