Lucas Brotz

When it comes to jellyfish, Lucas Brotz is rapidly making a name for himself as an international expert. Even David Suzuki called him ‘Canada’s foremost jellyfish researcher.’ For the last ten years he has been studying the enigmatic invertebrates, gauging their populations and the growth of jellyfish fishing around the globe.

Brotz, who recently completed his doctoral degree at the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, spoke about jellyfish population dynamics, jellyfish fisheries, his Michael A. Bigg Award for Student Research win, and the growing taste for jellyfish.

Are jellyfish populations on the rise?

Overall, yes, jellyfish populations are increasing.

Working with members of the Sea Around Us, and my supervisor, Dr. Daniel Pauly, we used a global network of sixty-six Large Marine Ecosystems and we found information on jellyfish populations for about forty-five of them. In those forty-five we found data for increasing populations in about 60% of them, over the last 60 years. While there were some areas were they were decreasing (about 10%) or remaining stable or so variable that there was no trend (30%), overall we are seeing a strong global trend of increases in jellyfish populations and jellyfish blooms. The other thing we noticed is that this increase is happening in disparate locations around the world. Not just in one location; we saw increases in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, also around Namibia in Africa, the Bering Sea, even Hawai’i and Antarctica.

What is causing this increase?

Some of the population changes are definitely linked to a number of anthropogenic factors. The big five are global warming, overfishing, pollution, coastal development, and translocation of invasive species.

Global warming sees the temperature of the water rising, causing some jellyfish to increase their reproduction or expand their ranges. Conversely, some jellyfish that thrive in cold waters may be negatively affected; however what we are seeing in many areas is a reduction in diversity of jellyfish types but an increase in abundance.

Global warming sees the temperature of the water rising, causing some jellyfish to increase their reproduction or expand their ranges. Conversely, some jellyfish that thrive in cold waters may be negatively affected; however what we are seeing in many areas is a reduction in diversity of jellyfish types but an increase in abundance.

A lot of fish eat jellyfish or are direct competitors for food and as the Sea Around Us figures show, we remove more than 100 million tonnes of fish from the oceans every year. This overfishing frees jellyfish from predation and competition, allowing their populations to build.

When pollution such as fertilizers and other chemicals enter the ecosystem, it causes eutrophication, basically a depletion of oxygen in the water. It is not that jellyfish thrive in low oxygen environments, but they are very tolerant, and can even store oxygen in their tissues, like a little scuba tank.

Coastal development has actually been a boon for jellyfish. As part of their reproductive cycle, many species develop larvae, which become polyps and then grow asexually into baby jellyfish. For polyps to grow they need the right environment; proper water temperatures, salinity, available food, etc., and in many cases they like to be right up underneath structures. So when humans develop a coastline there are huge amounts of shaded habitat – marinas, piers, breakwaters, infrastructure from oilrigs and aquaculture. On many structures all around the world scuba divers are going underneath and discovering they are brimming with jellyfish polyps.

Finally, translocation of invasive species is having a huge effect. If a shipping tanker pumps in water in one location, to use as ballast for example, they will pump that out in other locations and all the creatures that were in that water go with it. We’ve seen instances where a jellyfish that is not native to a sea or an ocean show up there and thrive, bloom out of control.

Humans are having a huge impact on jellyfish populations; how are jellyfish affecting us?

Well, everyone knows that jellyfish can sting people and so those numbers are increasing. They can interfere with a number of other industries as well, getting caught in fishers’ nets and intake pipes in boats. Every year we hear about power plants, built near the ocean to take advantage of cooling sea water, going into near meltdowns because of their intake pipes are clogged with jellyfish. They can also interfere with aquaculture farming.

On the plus side, they are also very helpful. They are food for a lot of marine creatures, fish, even the critically endangered leatherback sea turtle that eats almost nothing but jellyfish.

Research on jellyfish has led to breakthroughs in biotechnology that led to a couple of Nobel Prizes. There has been some work with jellyfish in the biomedical world, looking at how it can be used for arthritis research and in cancer research. They have been investigated for their material properties in construction, and they are also huge tourist attractions, both in their natural environment and in aquariums. They are fishmeal for farm animals, like chickens and pigs. And they are also being fished specifically as food for humans.

Jellyfish fisheries are becoming pervasive around the globe.

Fishers prepare to unload their catch in Ecuador, photo by Evelyn Ramos

There have been at least 20 countries involved in jellyfish fisheries, either in the past or currently, and that number is growing. Jellyfish have been served for a very long time, mainly in Asia, but spreading around the world. We are consuming many more jellyfish than people actually think; the global catch of jellyfish for human consumption is now exceeding 1 million tonnes. That is pretty significant because it exceeds the catches for what we consider popular seafood here in North America, like scallops or lobster.

The major jellyfish fishery is in China; they catch more than half the world’s consumption. Jellyfishing also occurs in other Asian countries including Japan, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines. We are now seeing them develop in Mexico, Ecuador in South America, even one in the United States where a number of shrimpers in the Gulf of Mexico have converted their boats and at certain times of the year to fish for jellyfish.

Certainly in the Americas, the jellyfish fishing industry is in its early stages. It has varying degrees of success in the USA and especially Mexico, proving to be a boon for local fishers, however no market has yet developed for jellyfish from fishing nations like Argentina, Peru, or Canada.

How is jellyfish eaten?

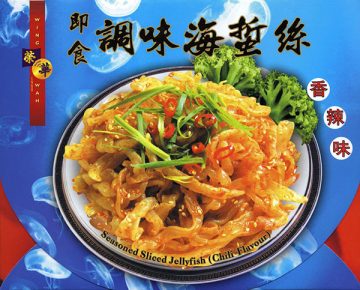

The most common way to serve jellyfish is thinly sliced into strips and served on its own with some soy sauce or sesame oil, or as an ingredient to a more elaborate dish like a stew. They have a taste of the sea, and the salts or chemicals used in processing, with a unique texture – chewy and crunchy. It reminds me of al dente pasta.

The most common way to serve jellyfish is thinly sliced into strips and served on its own with some soy sauce or sesame oil, or as an ingredient to a more elaborate dish like a stew. They have a taste of the sea, and the salts or chemicals used in processing, with a unique texture – chewy and crunchy. It reminds me of al dente pasta.

Even within the Asian market there are variations; the Japanese prefer a bit more crunch than the Chinese, so it depends on the species, the recipes and the target market. Here in Vancouver you can go to Chinatown and get a package to thaw or soak overnight. There are even snack products that you can buy and eat right out of package.

Still, I think there is a lot of work to be done by food scientists and food engineers to figure out what are the best ways to prepare and serve edible jellyfish. And as for it catching on with North American consumers, I am not sure it will happen any time soon.

Congratulations on winning the Michael A. Bigg Award for student research.

Lucas Brotz wins Michael A. Bigg Award

I am very humbled. To receive this from the Coastal Ocean Research Institute and the Vancouver Aquarium is a huge honour – I did my undergraduate degree in astrophysics and wanted to be an astronaut, and then I worked at the Aquarium and realized that underwater and outer space were very similar. Both are unexplored realms, inhospitable to humans, with no oxygen. We know more about the surface of the moon than we do about the ocean floor, and that really piqued my interest. To come back many years later and to be acknowledged by the Aquarium, a place that helped shaped my career, is a wonderful validation.

From astronaut to aquanaut

We have yet to find an alien in outer space, but underwater, I can’t think of a more alien creature than the jellyfish. It has been a pleasure to study them and there is so much more to learn.

Tags: Daniel Pauly, IOF postdoctoral fellows, IOF students, jellyfish, Lucas Brotz, Sea Around Us